Midsummer Christmas: The Nativity of St John the Baptist

Some years ago there was an exhibition at Hampton Court palace, one time home of Cardinal Wolsey before he gave it to Henry VIII in a failed attempt to stop himself falling from favour, which included a model of the great kitchen as it may have looked in the first half of the sixteenth century on 23rd June, the Vigil of the Feast of the Nativity of St John the Baptist. The buzz of activity was almost palpable: figures were to be seen scurrying around laden with platters of meat and vats of wine; the roasting fires were stoked high and sauces were being ladled onto whole boars as they were turned on the spits by the spit-boys; already-roasted pheasants were being decorated once more with their plumage; the steward could be seen gesticulating and giving orders; whilst the pantler, baker, wafer maker, brewer, poulterer, fruiterer, and a whole army of lower servants and kitchen maids, were busily in evidence amid the hustle and bustle of one of the most hectic days of preparation in the calendar. All had to be in place before the Earl Marshal came to inspect the proceedings ahead of the banquet which would begin as soon as the King returned from a day’s hunting.

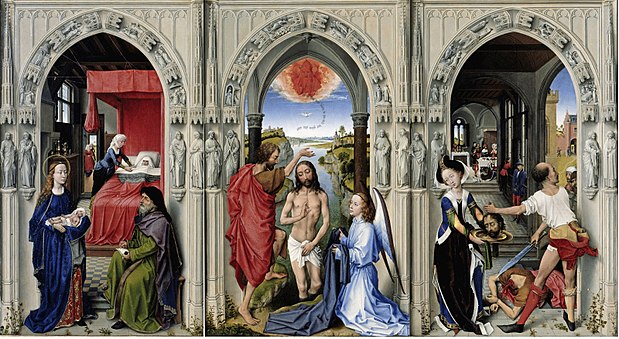

Beyond the palace, St John’s day was marked with pomp and ceremony as well as, at times, with vulgar celebration. There were festive fires and processions, dramatizations of the Saint’s life and death and the staging of Mystery Plays, there were songs, and games, and revels.

In the Middle Ages, and right up to the early modern period, St John the Baptist featured far more prominently in popular devotion than he does today. Many churches were dedicated to him (including some pre-Reformation churches that are now dedicated to St John the Evangelist), and images of him, in the form of statues and stained-glass windows, were to be found in almost every church. His feast day was preceded in Germany, from AD 1022 onwards, with a fortnight of fasting and abstinence, and from the Council of Agde (in modern-day southern France) in AD 506 the feast became a Holy Day of Obligation, when the people abstained from servile work and priests celebrated three Masses, one at midnight, one at dawn, and one during the morning, just as at Christmas. Indeed, the Feast of St John’s birth was, to all practical intents and purposes, a midsummer Christmas.

This mirroring of the Christmas festivities was not accidental. Not only did it allow for a great holiday halfway through the year, it also heralded an important event in the history of our salvation.* In the Christian liturgical calendar, a saint’s feast day is ordinarily observed on the day of his or her death, that is, on the day that he or she is born into heaven. Even so, there are three birthdays that are celebrated throughout the year, that of Our Lord at Christmas, of course, that of the Blessed Virgin on 8th September (nine months after the feast of her Immaculate Conception), and that of St John the Baptist. The first two seem obvious to any Catholic, but why should John the Baptist get special treatment? The answer is not so much that John was a cousin of Our Lord’s, after all, there are several of His cousins mentioned in the Gospels. The answer is to be found in the story of his annunciation and in the Visitation of Mary to her kinswoman Elizabeth, St John’s mother.

When the Archangel Gabriel appeared to Zechariah in the Temple as he took his turn at the priestly duties, the message proclaimed that Elizabeth, though herself in old age, would conceive and bear a son. There would be joy and gladness, and ‘many shall rejoice at his birth’ (Lk 1:14). Moreover, his named was to be called John, a name which means Graced by God, or God is Gracious, and ‘he shall be great before the Lord… and he shall be filled with the Holy Spirit even from his mother’s womb. And he shall convert many of the children of Israel to the Lord their God’ (vv.15-16).

Six months later, the Archangel again appeared, this time to a woman called Mary in the town of Nazareth, announcing that she, too, would conceive and bear a son. As soon as the angel departed from her, Mary rose and went into the hill country, and entered the house of Zechariah and Elizabeth where she greeted her kinswoman. And here, we have the answer to our question. We are told that as soon as Mary’s greeting reached Elizabeth, ‘the infant leaped in [Elizabeth’s] womb. And Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Spirit’ (Lk 1:41). In other words, St John the Baptist was deemed to have been baptized by the Holy Spirit whilst he was still in his mother’s womb. As a result, he was one of only three people in history – along with Our Lord and the Blessed Virgin – ever to have been born already filled with grace. St Joseph is deemed never to have sinned throughout his life, but even he was not born already in a state of grace, whereas St John both was born in a state of grace and he preserved his baptismal innocence right up until his martyrdom under King Herod. **

St John the Baptist is the great Precursor of the Divine Saviour, the Herald of the Messiah. He it is who was to proclaim and make known the coming of the Incarnate Word of God and to prepare God’s People for their long-awaited salvation. In other words, along with the birth of the Blessed Virgin and of Christ Himself, St John’s birth both heralded and actually began to usher in a new era. Whilst symbolism is involved in St John’s birth, nonetheless his nativity – along with the other two nativities – went beyond the merely symbolic and actually accomplished the inauguration of the new creation, the creation in the order of grace.

If the age-old tradition is correct, that Mary bore Jesus when she was only about fourteen years old, then, in the space of around fourteen years, we have all three grace-filled births that inaugurated ‘the acceptable time… the day of salvation,’ as St Paul calls it (2 Cor 6:2). And it is noteworthy that the number fourteen, as the double of the perfect number seven, signifies perfect holiness and salvation, for example, it was on the fourteenth day of the month of Nissan that the Angel of Death passed over the houses of the Israelites in Egypt and so began their deliverance from slavery (Ex ch. 12).

This, then, is what we celebrate with the feast of Midsummer Christmas, namely the nativity of the one whose birth heralds the coming of Our Saviour in just six months’ time. Truly, with the Church and in the words of the Benedictus, we can sing today,

‘And you, child, will be called the prophet of the most high; for you will go before the Lord to prepare His ways, to give knowledge of salvation to His people in the forgiveness of their sins, through the tender mercy of our God, when the day shall dawn upon us from on high to give light to those who sit in darkness and in the shadow of death, to guide our feet into the way of peace’ (Lk 1:76-79).

*24th June was not chosen for the feast in order to Christianize the pagan summer solstice as some claim. After all, it was only from the introduction of the Gregorian calendar in 1582 that the solstice fell around 23rd/24th June. Instead, and according to the old Roman way of counting dates, just as Christmas was kept on the eighth day before the Kalends of January, so St John’s Day was kept on the eighth day before the Kalends of July which, as June has only thirty days, brings us to 24th June.

** The Clever Boy will add that the Orthodox celebrate September 23rd as the Conception of St John, making a further parallel with the births of Our Lord and Our Lady and their antecedent conceptions in March 25th and December 8th

No comments:

Post a Comment