The only

colour image of what worship in Westminster Abbey looked like on the eve

of the Reformation has been plucked from the miles of shelving in the

Bodleian Library, Oxford, and shown to the world, or at least to the

readers of that excellent periodical The Westminster Abbey Chorister.

It is a wonderful picture, taken from the mortuary roll of John Islip, Abbot of Westminster, who died in 1532. He was important in the world and also stood for the dignity of the abbey of Benedictine monks. So his funeral was impressive.

The picture shows a part of the Abbey well known from royal weddings: the high altar against the screen that hides any view of the sacred chapel of St Edward the Confessor. On state occasions the altar is usually laid with huge bits of gold plate, like a sideboard.

It is quite otherwise in the Islip picture, being bare but for two candlesticks and a service book. On the wall behind it is a painting of the crucifixion, and above it hangs a strange object, which is explained in The Westminster Abbey Chorister by Matthew Payne, the Keeper of the Muniments at the Abbey. It is a cylindrical rose-coloured veil of silk bound around its upper part by a sort of triple tiara of gold. This is the cover for the hanging pyx, the metal casing in which the Sacrament was reserved.

High above the altar stands an arrangement of painted figures that featured in most churches: the rood. In the centre is Christ on the cross, flanked by his mother Mary and St John. These are in turn flanked here by two angels – the kind with six wings, seraphim, I suppose. Below the rood and above the altar projects a blue-coloured tester functioning like a baldacchino to shelter ritually the sacred altar.

The difference on the May day that the picture depicts was the presence before the altar of the great hearse of Abbot Islip, surrounded by black-habited monks and 24 men carrying torches. By hearse was not meant a thing with wheels, or even a carrying-bier. In this case it was a soaring framework that canopied the draped coffin and acted as a vast chandelier. A “chapelle ardent” was a name Garter King of Arms used for it two centuries later. On four high finials and a central spire (of gilt and painted woodwork) were dozens and dozens of beeswax candles. I can’t imagine how they were lit. Perhaps by taper in a long stick like a fishing-rod.

Inscribed above the altar is: Adoramus te, Christe, et benedicimus tibi – “We adore thee O Christ and we bless thee.” All present would have known the response: Quia per crucem tuam redemisti mundum – “Because by thy cross thou hast redeemed the world.”

That antiphon was familiar, not from the devotion called the Stations of the Cross, which was widely popular in churches only later. It was known from the solemn liturgy for Good Friday, chanted at the ceremony of the Adoration of the Cross, known in English as Creeping [to] the Cross. Shakespeare knew it, writing anachronistically in Troilus and Cressida of how “they used to creep, to holy aultars”. People would come forward and kneel and kiss the wood of the cross, in worship of Christ who hallowed it.

It would have been quite suitable for the inscription to have been above the altar all the time, since the Masses said below related to the sacrifice of the cross. But it’s possible it was rigged up just for the funeral.

The picture is a copy, carefully made in 1743 by George Vertue, engraver to the Society of Antiquaries, from an original kept by John Anstis, Garter King of Arms. It’s fortunate that Vertue made the copy, for the original has been lost.

It is a wonderful picture, taken from the mortuary roll of John Islip, Abbot of Westminster, who died in 1532. He was important in the world and also stood for the dignity of the abbey of Benedictine monks. So his funeral was impressive.

The picture shows a part of the Abbey well known from royal weddings: the high altar against the screen that hides any view of the sacred chapel of St Edward the Confessor. On state occasions the altar is usually laid with huge bits of gold plate, like a sideboard.

It is quite otherwise in the Islip picture, being bare but for two candlesticks and a service book. On the wall behind it is a painting of the crucifixion, and above it hangs a strange object, which is explained in The Westminster Abbey Chorister by Matthew Payne, the Keeper of the Muniments at the Abbey. It is a cylindrical rose-coloured veil of silk bound around its upper part by a sort of triple tiara of gold. This is the cover for the hanging pyx, the metal casing in which the Sacrament was reserved.

High above the altar stands an arrangement of painted figures that featured in most churches: the rood. In the centre is Christ on the cross, flanked by his mother Mary and St John. These are in turn flanked here by two angels – the kind with six wings, seraphim, I suppose. Below the rood and above the altar projects a blue-coloured tester functioning like a baldacchino to shelter ritually the sacred altar.

The difference on the May day that the picture depicts was the presence before the altar of the great hearse of Abbot Islip, surrounded by black-habited monks and 24 men carrying torches. By hearse was not meant a thing with wheels, or even a carrying-bier. In this case it was a soaring framework that canopied the draped coffin and acted as a vast chandelier. A “chapelle ardent” was a name Garter King of Arms used for it two centuries later. On four high finials and a central spire (of gilt and painted woodwork) were dozens and dozens of beeswax candles. I can’t imagine how they were lit. Perhaps by taper in a long stick like a fishing-rod.

Inscribed above the altar is: Adoramus te, Christe, et benedicimus tibi – “We adore thee O Christ and we bless thee.” All present would have known the response: Quia per crucem tuam redemisti mundum – “Because by thy cross thou hast redeemed the world.”

That antiphon was familiar, not from the devotion called the Stations of the Cross, which was widely popular in churches only later. It was known from the solemn liturgy for Good Friday, chanted at the ceremony of the Adoration of the Cross, known in English as Creeping [to] the Cross. Shakespeare knew it, writing anachronistically in Troilus and Cressida of how “they used to creep, to holy aultars”. People would come forward and kneel and kiss the wood of the cross, in worship of Christ who hallowed it.

It would have been quite suitable for the inscription to have been above the altar all the time, since the Masses said below related to the sacrifice of the cross. But it’s possible it was rigged up just for the funeral.

The picture is a copy, carefully made in 1743 by George Vertue, engraver to the Society of Antiquaries, from an original kept by John Anstis, Garter King of Arms. It’s fortunate that Vertue made the copy, for the original has been lost.

The Abbot was clearly aboy from the Abbey's estate at Islip who took, as did many other monastics at the time, their birthplace as their new patronymic upon entering their chosen community. As the Abbey weblink below shows he entered as a novice aged 16 in 1480 and was elected to head the monastery in 1500 when he was 36. As Abbot he oversaw the construction of what is now known as King Henry VII's Chapel between 1503 and 1516.

Image; Look and Learn

The Clever Boy will point out in his cleverness that Christopher Howse is wrong when he says the original is lost - it is part of the Abbot's Mortuary Roll and has been published by the Society of Antiquaries. The surviving original - and Vertue's copy can be seen to be very accurate - is a drawing and does not reproduce well in online methods.

As the website for The Antiquaries Journal points out the mortuary roll of John Islip (1464–1532), Abbot of Westminster, is the finest example of its kind to survive in England. The drawings, possibly by Gerard Horenbout, afford the only views of the interior of Westminster Abbey before the Dissolution. The discovery of eighteenth-century copies of an unknown, coloured version of the roll provides important new evidence for both the circumstances of the production and the later history of both rolls. It also provides, for the first time, an authentic colour view of the interior of Westminster Abbey in the late medieval period, and new information on its decoration.

The always excellent Westminster Abbey website has the following account of the Abbot and his Jesus chantry at John Islip. There is a detailed illustrated account of the chantry and the depiction of it in the Islip Roll in John Goodall's 2011 article from the Journal of the British Archaeological Association which can be viewed at The Jesus Chapel or Islip's Chantry at Westminster Abbey

The hangings covering the tombs on the north side of the Sanctuary is a tradition that survives on the continent in Italy, Malta and Spain on special occasions. It is said that theiron brackets in the nave of Winchester Cathedral were installed to hold hangings for the wedding of King Philip and Queen Mary in 1554, and the engraving of the coronation of King Charles II in 1661 suggests similar hangings in Westminster Abbey on that occasion.

Of the reredos as depicted only the stone lower third survives, and is usually dated to the reign of King Edward IV, so it was a new part of the abbey church. The Rood and its flanking figures are very much in the style recreated by Sir Ninian Comper in the twentieth centuries in churches such as Wakefield Cathedral and Wymondham Abbey.The colour scheme as recorded in Vertue's copy is a valuable addition to our knowledge of the interior of the monastic church - unless this is an improvisation by the eighteenth century copyist.

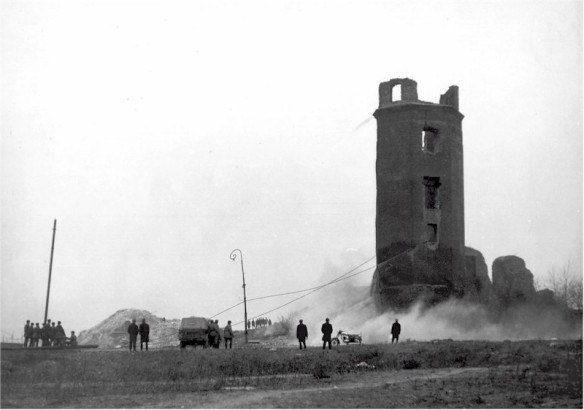

The funeral hearse with its candles was a tradition that survived - as in this example for 1958:

The funeral catafalque for Pope Pius XII in St Peter's in 1958

As the website for The Antiquaries Journal points out the mortuary roll of John Islip (1464–1532), Abbot of Westminster, is the finest example of its kind to survive in England. The drawings, possibly by Gerard Horenbout, afford the only views of the interior of Westminster Abbey before the Dissolution. The discovery of eighteenth-century copies of an unknown, coloured version of the roll provides important new evidence for both the circumstances of the production and the later history of both rolls. It also provides, for the first time, an authentic colour view of the interior of Westminster Abbey in the late medieval period, and new information on its decoration.

The always excellent Westminster Abbey website has the following account of the Abbot and his Jesus chantry at John Islip. There is a detailed illustrated account of the chantry and the depiction of it in the Islip Roll in John Goodall's 2011 article from the Journal of the British Archaeological Association which can be viewed at The Jesus Chapel or Islip's Chantry at Westminster Abbey

The hangings covering the tombs on the north side of the Sanctuary is a tradition that survives on the continent in Italy, Malta and Spain on special occasions. It is said that theiron brackets in the nave of Winchester Cathedral were installed to hold hangings for the wedding of King Philip and Queen Mary in 1554, and the engraving of the coronation of King Charles II in 1661 suggests similar hangings in Westminster Abbey on that occasion.

Of the reredos as depicted only the stone lower third survives, and is usually dated to the reign of King Edward IV, so it was a new part of the abbey church. The Rood and its flanking figures are very much in the style recreated by Sir Ninian Comper in the twentieth centuries in churches such as Wakefield Cathedral and Wymondham Abbey.The colour scheme as recorded in Vertue's copy is a valuable addition to our knowledge of the interior of the monastic church - unless this is an improvisation by the eighteenth century copyist.

The funeral hearse with its candles was a tradition that survived - as in this example for 1958:

The funeral catafalque for Pope Pius XII in St Peter's in 1958

Image: romanitaspress.com

It also survived, but without candles, in the tradition of the Duke of Wellington's funeral car on 1852 and in the Habsburg Death Coach in Vienna.

I have always liked the little detail of the bedesman or taperer relighting his torch in the foreground of the Islip Roll - one knows that feeling of "Why does my taper have to be the one to go out...?"

This was 1532 - within months, if not indeed already, such ritual and ceremonial was going to come into question and under attack - not unlike 1958 come to think of it. Abbot John Islip and Pope Pius XII were at least spared seeing that in their earthly lifetimes.