Sunday, 31 March 2024

Easter Day

Saturday, 30 March 2024

Fr Hunwicke on the Exsultet

Conserving the Breamore Rood

Hot Cross buns

Thursday, 28 March 2024

The Ambrosian Rite for Holy Thursday

Papal Ceremonies for Maundy Thursday

A Scottish equivalent to the Royal Maundy

June 2 [1607]. – The Privy Council refer to ‘a very ancient and lovable custom’ of giving a blue gown, purse, and as many Scotch shillings as agreed with the years of the king’s age, to as many ‘auld puir men’ as likewise agreed with the king’s years; and seeing it to be ‘very necessary and expedient that the said custom should be continuit,’ they give orders accordingly.

Sunday, 24 March 2024

Patristics for Palm Sunday

Quite apart from their apposite wss at this point in the liturgical year they are also fine examples of the style of both authors.

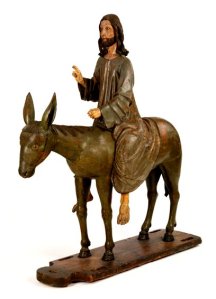

The Palmesel

‘Christ on the Ass’, c. 1480. Limewood and pine, painted and gilded. Southern Germany. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Image:jasongoroncy.com

Palm Sunday - The Entry into Jerusalem

Saturday, 23 March 2024

Medieval spectacles

Thursday, 21 March 2024

Keeping medieval cities clean and fragrant

Monday, 18 March 2024

A Greek visitor to Eboracum

Sunday, 17 March 2024

The restored murals at the Oxford Oratory

Saturday, 16 March 2024

More about this year’s Constable’s Dues

Wednesday, 13 March 2024

The Constable’s Dues

Tuesday, 12 March 2024

Reassessing Silchester

Saturday, 9 March 2024

Kit bags across the centuries

Le combat en armure au XVe siècle looks at the flexibility that is possible and Can You Move in Armour? reconstructs the fitness routine - or showing off - of Jean Le Maingre, Maréchal Boucicaut, who was taken prisoner at Agincourt, and died a few years later as a captive in England.

Thirdly there is also, to show the comparison with modern equipment, the superb, and almost hypnotic, Obstacle Run in Armour - a short film by Daniel Jaquet

Friday, 8 March 2024

The relics of St Thomas Aquinas

Thursday, 7 March 2024

St Thomas Aquinas 750

Tuesday, 5 March 2024

The late arrival of a Faroese jumper

Monday, 4 March 2024

Policing morals at Cambridge University - and at Oxford

Saturday, 2 March 2024

Hoping to save a twelfth century ivory for the nation

The article then goes on to look at British regulations regarding art exports, and compares them with those in France, Germany, and Italy about safeguarding heritage objects and preventing their loss overseas.

The article then goes on to look at British regulations regarding art exports, and compares them with those in France, Germany, and Italy about safeguarding heritage objects and preventing their loss overseas.