King and Conqueror’s most gruesome death should never have happened and would be “totally out of character”

If there is anyone whispering in his ear, it is his mother, Emma of Normandy.

The real Emma was queen consort to both Aethelred the Unready and Cnut the Great, the only woman to have married two English kings. Two of her sons were also kings, first Harthacnut, and then Edward the Confessor. For her whole life, she had been an able political player.

In King and Conqueror, she is vicious and manipulative, a woman who dominates Edward and goads him for his failures. She is the power behind his throne.

When Edward finally snaps, he does so totally and utterly. In a moment of red mist worthy of Game of Thrones, he beats his mother to death with his crown.

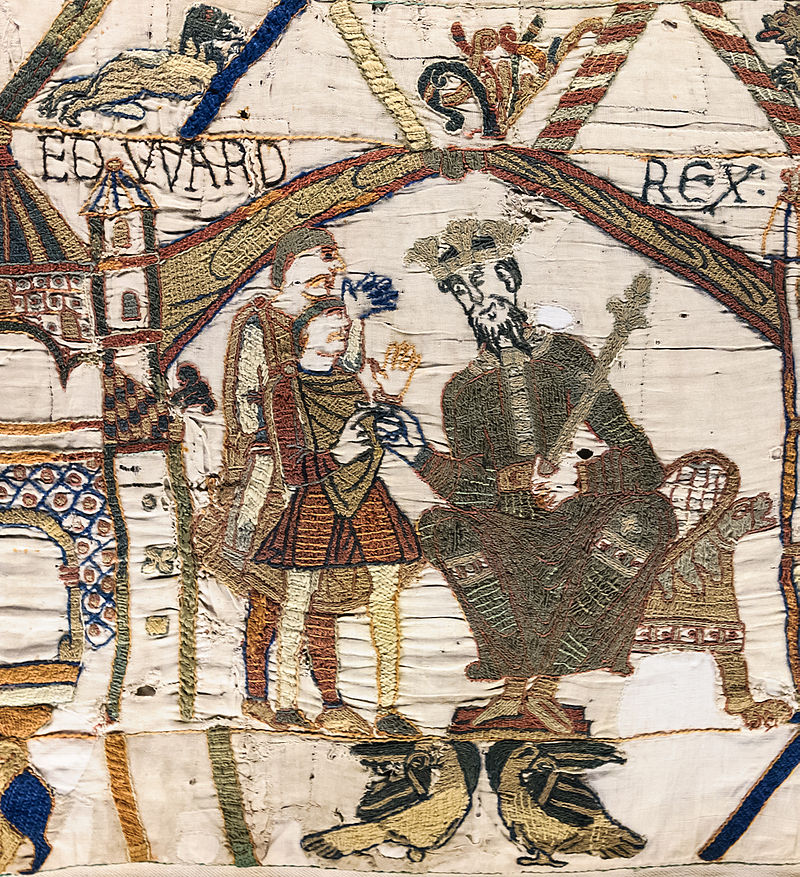

Did Edward the Confessor beat his mother Emma of Normandy to death with this crown?

“Beating someone to death with his own crown? I mean, no, I don't think Edward did that, not to his mother.”

That’s the view of historian Tom Licence, who was speaking to us while recording an episode of the HistoryExtra podcast on Edward’s life.

“We can't be absolutely certain, but that would be totally out of character and wouldn't fit with my understanding of their of their relationship”

That’s the view of historian Tom Licence, who was speaking to us while recording an episode of the HistoryExtra podcast on Edward’s life.

“Edward's way of punishing people was to take away their assets or to put them into exile. He hit them in the pocket, not over the head,” says Licence.

“He was not that sort of ruler. I could imagine Cnut the Great doing that. I could definitely imagine Aethelred the Unready doing that.”

Aethelred the Unready was Edward’s father, and the man behind the St Brice’s Day Massacre of 1002 – the attempted slaughter of all the Danes living within his lands as revenge against the Viking incursions. Cnut was the king who claimed the throne through during the Danish Conquest of 1016, which is why Edward spent his youth in exile in Normandy.

What happened to the real Emma of Normandy?

There’s no record that the real Emma of Normandy was murdered, by her son or otherwise – but she was removed from the royal court.

Emma had all the cards before Edward becomes king, but there's a very clear turnaround, says Licence.

“As soon as Edward gets on the throne, Emma's power is broken. He takes away her wealth, he deposes her favourite bishop, her lands are removed from her and she's sent, pretty much into retirement to Winchester, where she lives out her days”

Emma died in Winchester of an unknown cause in 1052, almost a decade after she was sent there. “There's a good 10 years where she's doing nothing and has no influence whatsoever,” Licence points out.

But there may have been another woman guiding Edward after Emma was removed from court – his wife, who happened to be Harold Godwinson’s sister.

“The way I see it, Edith of Wessex, takes over [Emma of Normandy’s mantle]. Emma ceases to appear on the charters. Edith appears, and she is the one who's there at his councils and helping him make his decisions.”

It was Edith who commissioned a tract called The Life of King Edward, which is one of the prevailing sources for our view of Edward as a pious ruler.

Edith, whom Edward marries in 1045, is the person who's orchestrating his theatricality,” says Licence.

“She embroiders his garments, she commissions goldsmiths to make all the jewels that he wears, and she ensures that when he walks on stage in front of the public … he looks like a saint, like some patriarch from the Old Testament, like someone almost divine.”

What was Edward’s relationship like with his mother?

While the real Emma and Edward may not have been at each other’s throats, historian Tom Licence characterises their relationship as being distant and predominantly political.

“Today we might think of this in terms of parental neglect or a mother not looking after her son as she should,” says Licence.The

“And what Edward felt was that all through those years in exile she hadn't done enough to support him, to promote his claim to the throne, to help him come back to England.”

What Emma had done instead was marry Cnut – and then had children with him.

“He had become king in Edward's place, so you could just imagine how Edward would be feeling, how his mother had maybe betrayed him and allowed her new son to replace him – almost like a cuckoo in the nest.”

Nonetheless, Licence doesn’t think that sense of betrayal would manifest into physical violence. He does, however, have a theory as to why Edward was depicted this way in King and Conqueror.

“A previous biographer who didn't like Edward very much wrote that he was the sort of man who probably beat his wife. I don't think that's justified, or that we have any warrant for that.

“And beating to death Emma, with a crown? No, no. Just, no.”

Rather than using photographs from “King and Conqueror” I have added here an eleventh century depiction of Queen Emma