Last week I posted about the 700th anniversary of the battle of Boroughbridge in 1322 and finished it with Thomas Earl of Lancaster awaiting his fate as a defeated rebel at the hands of his cousin King Edward II as he was conveyed from the battlefield to York and then to his castle at Pontefract.

There is a good account of the Eatl’s life from Fourteenth century fiend at A Royal Traitor: The Life & Execution of Thomas of Lancaster

Thomas arrived - whether by road or brought along the rivers Ouse and Aire - at Pontefract on March 21st. The Anonimalle Chronicle records that he was “contemptuously insulted … to his face with malicious and arrogant words” by the King and the Despensers. He was held overnight in a tower he was rumoured to have built with a view to imprisoning the King in it. This is often identified with the Swillington Tower on the northern side of the castle. However this extra-mural structure appears not to have been built until about eighty years later.

King Edward II in no mood to forgive his cousin and his supporters who must also have arrived with Earl Thomas to learn their fate. Given that the King had more than a decade of frustration at his opponents to drive him forward, and that they had been in active rebellion, they can have little doubt as to what that would be.

The following day, on March 22nd, Lancaster was led into the hall of his own castle to face the King and those selected to judge him. The King stood and recounted Thomas’ offences, and thus, tried on the King’s Record, which set out his obvious prima faciae guilt and with a bench of uniformly hostile peers he was sentenced to a traitor’s death. Thomas’ response of “Shall I die without answer?” ie being able to make a defence was inevitably ignored.

Queen Isabella interceded to mitigate the punishment to mere beheading rather than hanging, drawing and quartering. This was often the expected role of the King’s consort - and she was also Thomas’ niece, as her mother, Queen Joan of Navarre, wife of King Philip IV of France, was the Earl’s elder half-sister.

Presumably after Thomas’ fellow defendants had been as expeditiously condemned, but with no mitigation of their punishment, they were sent to their executions. Humiliation was further heaped upon the fallen Earl, led on horseback with his face to the animal’ tail, he was accompanied by a Dominican friar, presumably from the priory innthr town, out of the castle , past the Cluniac priory and up to the ‘Thieves Gallows’ above the main road to Ferrybridge and places to the north. Presumably the other condemned men who were to be executed with him followed others followed on. The other condemned men were sent to their county towns or similar to suffer.

Having dismounted, and before, or according to one account, after the hanging, drawing and quartering, of six of his followe, Thomas knelt facing east. He was then made to face north towards Scotland and his implicit links there and a “Villein of London” beheaded him. The near contemporary sources suggest the use of a sword and perhaps more than one stroke being employed.

Afterwards the Prior of the Cluniac house of

St John begged the Earl’s remains and they were interred in the Priory church - the house was very much under the patronage of the Lacy and Lancaster lords of Pontefract.

Apart from the executions in York and elsewhere of Thomas’ adherents the King marked his victory by summoning Parliament to York which revoked the Ordinances which had been imposed upon him a decade before and which had been championed by Lancaster. This legislation, the Statute of York, is set out in the link to Revocation of the New Ordinances (1322)

This marks the beginning of what is Oren termed the Tyranny of King Edward II - for which I would recommend Natalie Fryde’s book of the same name - and the King was not slow to seize the estates of Lancaster - and of his estranged wife, Countess Alice - as well as those of other noblemen anf their wives. If for a fairly brief while the King could enjoy the fruits of victory he was fuelling discontent and the memory of his defeated and executed cousin.

Meanwhile at Pontefract a cult of the dead Earl was developing. Dr Maddicutt in his biography of Thomas writes of the “almost repulsive” character of his subject as both political leader and as an individual. His reputation according to contemporaries was as promiscuous and one noted for casting his female conquests aside. Although he had no legitimate heirs he fathered two illegitimate sons, one of whom, called John of Lancaster, became a theologian.

Nonetheless Thomas began to be seen as a saintly figure, as a martyr

It says perhaps something as to how unpopular King Edward II and his close advisors the Despensers were that this movement developed so rapidly and so widely. This was I think more so than that of than Simon de Montfort at Evesham following his death and burial there in 1265.

Within a short time of Thomas’ execution a group of Gascon soldiers had to be sent to keep pilgrims way from the execution site on what came sooner or later to be known as St Thomas’ Hill. Devotion of his memory was not confined to Pontefract and the north. In 1323 the government was ordering the removal of a tablet commemorating the Earl in St Paul’s in London. This may have been the exemplar of the lead cut out panels of which some survive and which tell the srltory of the Earl’s defeat and death.

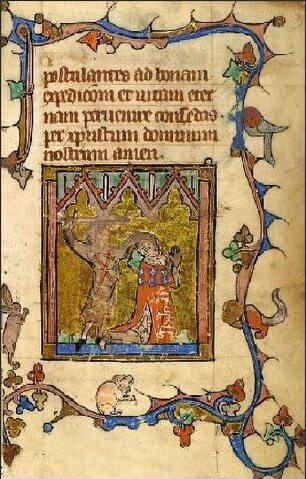

This devotion only grew after the toppling and abdication of the King 1326-7. In 1327 there was a petition from Parliament to Pope John XXII for the canonisation of Thomas. Pilgrimages on their behalf were funded by the aristocracy to Pontefract, Books of Hours included Thomas in their calendars anf illuminations and the complicated lead wall plaques were clearly worth making.

Discussion of this and other aspects of the cult in an illustrated post on The History Blog in 2015 which can be seen at The History Blog » Blog Archive » Rare Earl of Lancaster devotional panel found on Thames riverbank

A Book of Hours in the Douce MS 231 in the Bodleian image pairs the Earl with St George:

Image: Wikipedia

If Thomas was paired with St George in a Book of Hours then at South Newington in Oxfordshire about 1330 a new pair of wall paintings placed him alongside St Thomas of Canterbury in their status as martyrs.

The remains of the South Newington painting,

Note the blood spurting from an initial cut on Thomas’ neck.

Image: reed design. co.uk

At Pontefract it appears likely that the entire eastern arm of the priory church was rebuilt on the proceeds of the offerings at Thomas’ tomb and it has been described as being for a period the most fashionable place of pilgrimage in the realm. In 1359 blood was reported to have flowed from the tomb and in 1361 a chapel was erected by a long-standing Lancastrian servant Simon Symeon on the site of the martyrdom. This stood within an enclosure and in the 1940s some carved stonework was found on the site. The chapel disappeared at the reformation and a windmill occupied its site until the twentieth centur.

Antiphon: Oh Thomas, Earl of Lancaster,Jewel and flower of knighthood,Who in the name of God,For the sake of the state of England,Offered yourself to be killed.Versicle: Pray for us, soldier of Christ.Response: Who never held the poor worthless.Collect: Almighty everlasting God, you who wished to honor your holy soldier Thomas of Lancaster through the lamentable palm of the martyr for the peace and state of England just as he is lead through the sacrament for God’s own exceeding glory [and] through your holy miracles. Bestow, we pray, that you grant all faithful venerating him a good journey and life eternal. Through Christ our Lord, Amen.

This presents a distinctly much more favourable image of the Earl than that of either King Edward II or most modern historians and does indicate why he was regarded as worthy of veneration.

This illumination of the beheading of the Earl is from the same manuscript

Image: Bridewell Library/english monarchs.co.uk

The accession to the throne of the Lancastrian line in 1399 in the person of Thomas’ great great nephew King Henry IV appears to have maimed support for the cult at Pontefract. IOn his death in 1413 the King left a quantity of vestments to the priory there and his second son was named Thomas. In 1466 blood was again reported to have flowed from Thomas’ tomb. Was this seen as a comment on the dethronement of the house of Lancaster and the imprisonment of King Henry VI? The Prior of St John’s received the right to wear pontificals from Pope Alexander VI in the 1490s and at the dissolution of the house in 1539 it was, after the very wealthy priory at Lewes, the best endowed Clunic foundation in the country.

An early sixteenth century list and commentary on Yorkshire relics records the Earl’s belt - predictably of use for women in childbirth - and his hood. Perhaps this was one he wore to his death but it was believed to assist sufferers from migraine and “rye asthma” - hay fever - which leads one to wonder if Thomas himself suffered from them.

With one possible exception which I will consider below there is no contemporary portrait of Earl Thomas. We also lack literary descriptions other than the hints in the two nicknames given to him by Piers Gaveston.

These were “The Churl” and “The Fiddler”. The first, recorded in the English Brut was hardly respectful to the senior prince of the blood after the King and may indicate an awkward, ungracious or uncultured manner or a selfish reluctance to share. This might well accord with Maddicott’s view of Thomas.

The other one of the Fiddler was commented upon in the French version of Brut by a contemporary as vielers. This was said to have been inspired by Lancaster’s appearance because he was slim and tall ( porceo quil est greles et de bel entaile ). It has also been suggested that this might refer Lancaster having a manipulative nature.

There is more about all of Gaveston’s nicknames for his opponents at Piers Gaveston's Insulting Nicknames, and An Illegitimate Squire and at Those Insulting Nicknames

The one possible portrait is a carved head on the corbel table of the base of the shrine of

St Edburga from Bicester Priory and which is now in Stanton Harcourt church in Oxfordshire.

Dated variously to 1302, 1294-1317 and to before 1320 it has a series of costs of arms and heads above. These look as if they could be portraits. The arms and putative heads of Thomas and Alice side by side. He is shown with curly hair and beard and it could be a portrait.

The arms and portrait heads can be seen on this Flickr pohotogrsph - Countess Alice is on the right sbove the Lacy arms, and Earl Thomas to the left above his arms: Stanton Harcourt, Oxford, St. Michael's, shrine of St. Edburg, detail

Previous articles about Earl Thomas which I have posted and which give additional information can be seen at St Thomas of Pontefract from 2011, and there are three posts from 2012, St Thomas of Pontefract at South Newington, St Thomas of Pontefract in the British Museum and St Thomas of Pontefract in the Sellers Hours.

From 2014 there is The beheading of Thomas of Lancaster in 1322 which looks at an Italian depiction of his death in Villani’s Cronica Nuova

No comments:

Post a Comment