This last week I have written several pieces on this blog relating to the Peasants Revolt of 1381. To round off the theme here is a slightly revised version of an article I originally wrote last year and hoped to publish in a magazine. That has not come about so I have decided to reproduce it here. It is an attempt to make serious points in a slightly tongue-in-cheek assessment of, well, shall we say, the ties that bind…

The Dowry of Mary - Then and Now

The rededication last year of England as the Dowry of Mary may appear as fitting and suitable, a restatement of long-standing traditional national devotion, an endorsement of pilgrimage and prayer to Our Lady. Some may see it as merely picturesque, a sentimental link to King Richard II’s action over six centuries ago, but not of significant political or ecclesial import today. Yet that decision by Richard in during the Peasant’s Revolt in 1381 was of very considerable ideological significance in its own day, and we may miss the contemporary parallels at some risk to our understanding.

That the England of 1381 was very different from that of 2021 is obvious. In other, less obvious, ways the discrepancies are perhaps less than might be imagined. Whilst parallels cannot be pushed too far there may be quite a lot which is common to both eras. So what has changed?

The fourteenth century was in many ways as conflicted as is the early twenty first. Its complexity should not be underestimated. Our Information technology conscious society might recall a very significant and comparable change six centuries ago - the rise of English as a language of elite literature and record. This development - there being as yet no internet - was to be embraced by heretical lollards to disseminate their ideas, but also by that champion of orthodoxy Henry V.

Climate change is also nothing new. In the late fourteenth century the Northern Hemisphere was moving further into the so-called Little Ice Age, with a retreat from marginal lands, harsher winters and poorer summers becoming more likely and coastal inundations by the North Sea perhaps more frequent. The societal consequences of these changes were often far reaching and profound. Bad weather could be blamed on bad people and their actions or existence - political correctness is not new. Would a late medieval Greta Thunberg be a companion of St Bridget of Sweden or would she be burned as a witch?

Catholics may consider the late medieval period to have been an “Age of Faith”. Non-believers may consider it an “Age of Superstition”. Both may well be right, and equally both may well be wrong. Faith and superstition are often inextricably mixed or shackled together. That was true of England in 1381. It is not untrue of it in 2021.

Seeing it as an age of Faith may be wishful thinking, nostalgia for a reality that never really was. Certainly popular as well as elite devotion was widespread, strong and vivifying in a way that would seem remote or possibly incomprehensible to most modern Catholics, let alone others. The Church promoted, encouraged, supported a rich and varied spiritual life for the English, and manifested it in beautiful buildings, art and music. That quintessentially English gothic style we term Perpendicular was in its springtime producing masterpieces such as the cathedral naves of Canterbury and Winchester. Such projects and the production of devotional objects and furnishings must have formed a significant part of economic life.

Outwardly in 1381 the Church may have had confidence, but it also faced real uncertainties. Twenty odd years later Archbishop Arundel of Canterbury was scandalised when he witnessed members of the royal army turning away and ignoring the Blessed Sacrament as he carried it to sick troops when he was with the royal army at Worcester. Corpus Christi may have thrived as a devotion with active guilds and chapels - but clearly not everyone was engaged.

One person who undoubtedly had his reservations was the Oxford academic and heresiarch John Wyclif. Increasingly radical in his opinions he was eased out of Oxford in 1382 and died at the very end of 1384, and by now he was adding denial of Transubstantiation to his ever lengthening list of controversial and heretical opinions. Historians still seek to fully elucidate the transition from academic reflection to popular proto-protestant lollardy and to estimate its numerical strength. By 1395 these radicals were posting up their Twelve Conclusions in London, calling upon Parliament as it assembled to legislate. Succinct and shocking these were a full throated assault on most aspects of Catholic belief and practice. Papal authority, sacramental ordination, priestly celibacy, transubstantiation, sacramentals, secular work by the clergy, prayers for the dead, pilgrimages, private confession, military action, female celibacy and the use of images and the arts in the service of devotion are all condemned. Much of this was realised or became familiar with the sixteenth century assault on the Church, but modern cognates in the name of modernity, of ecumenism and in the wake of the abuse scandal spring readily to mind. For disendowment read the threats to charitable status and similar pressures.

Wyclif’s theology of Dominion - that only those who are foreknown to salvation or are spiritual can exercise lawful authority - has its modern secular equivalent in the frequent rush to condemn the politically incorrect for their perceived failings in meeting the latest contemporary mores.

Lollards may not have been the Liberation theologians of their day, but such a sweeping set of opinions was a novelty in England. This religious and political radicalism was seen by the influential historian K.B.McFarlane in the mid-twentieth century as the origin of English nonconformity. However it was usually more restrained in its millenarianism than contemporaneous movements on the continent. The communitarian and eschatological implications of Corpus Christi, which coincided with the rising, may indeed have fed into it drawing upon its themes to gather participants.

1381 was during the Great Schism which had erupted three years earlier with the election by the cardinals in 1378 of two rival Popes - Urban VI and Clement VII - and the consequent division on power-political lines of Europe between Urbanists and Clementists. That continued until 1417, and resolving the split spawned the Conciliar epoch, not to mention a period for a few years of three Popes competing for allegiance. Reunion with Byzantine Orthodoxy was a hope, and briefly attained in 1438-9. Today we have two Popes, even if they are in full peace and communion with each other, but union with Constantinople remains elusive.

Scandalous clergy, which alas there have always been, were and are naturally newsworthy and unduly prominent in records as their misdeeds were dealt with. A wide spectrum of predictable human misbehaviour emerges. Surprising in its perversity is the 1395 account given of his career and clerical contacts in and around London and Oxford by the transvestite prostitute John “Eleanor” Rykener (look him up on Wikipedia at John/Eleanor Rykener ) which might make many readers of modern tabloids blanch.

We need not doubt that there were many good priests. Historians such as William Pantin, Robin Storey and Jonathan Hughes have revealed a clergy that was well educated and pastorally sensitive but, as today, that rarely makes the news.

Radical clergy who did make the news in 1381 were those lesser clerics who were local leaders of revolt and who were to pay the ultimate price afterwards.

At a senior level the reaction to and of the hierarchy varied. Archbishop Sudbury of Canterbury, the Prior of the Hospitallers - both of them government ministers - and the Prior of Bury St Edmunds were beheaded by the rebels. Bishop Despenser of Norwich took an active part in suppressing the revolt by personally leading troops against them.

1381 was clearly a time of national division. The country was recovering and adapting with no little success after the Black Death over thirty years before. Catastrophic as it had been, the recovery was perhaps like that after WWII. By 1381 there was a sophisticated court and aristocratic culture, reasonable prosperity and an expanding cloth industry. Nonetheless there were deeply felt grievances and the Peasants Revolt was unparalleled in English history. Later popular revolts such as those of 1450, 1497, 1536, 1549 and 1569 seemingly had more focused, if still far-reaching, objectives - and the reality and complexity of the events of the 1381 rising should be neither underestimated or overestimated. As a French historian has written peasant revolts were to agrarian societies what strikes are to industrial ones. Sentimental simplifications should be avoided.

In 1381 popularism literally ran riot in London and a number of other towns. Today we have a newly confident political popularism as a legacy of Brexit. In 2019 the decisive votes in the General Election were in areas that felt they had been left behind and forgotten by the metropolitan elite. In 1381 the areas that rose in revolt were amongst the most prosperous and resented both the government’s fiscal interest in them and the lack of remedy for grievances. This was indeed a revolt by Essex man. The attitude to immigrants is instructive: when the peasants invaded London they targeted the Flemish traders - the failure to pronounce “bread and cheese” in the appropriate English way was likely to result in a cut throat.

Social tensions and strong regional differences are important in understanding the events of 1381. There was as yet no union with Scotland to be under threat, but in 1385 Richard II was to be the last English king to lead an invasion of Scotland. He was to pay two visits to his Lordship of Ireland in the 1390s, suggesting an engagement with it that few of his predecessors or successors were to show.

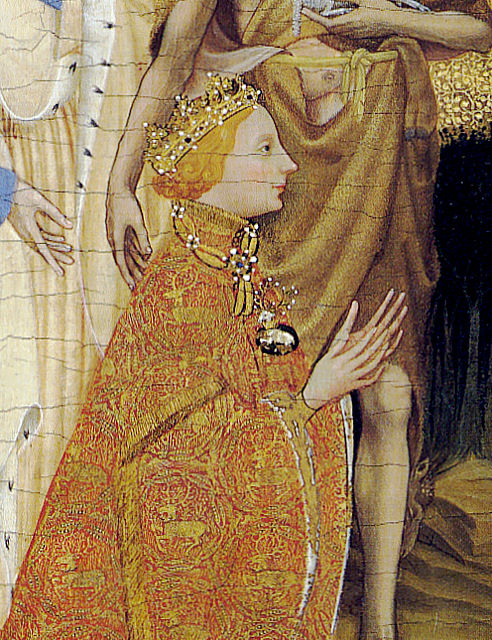

King Richard II as he may have appeared in 1381

From the Wilton Diptych painted in 1397

Image:ReedDesign

Central to the defeat of the uprising and to the dedication of England as the Dowry of Mary is the fourteen year old King Richard II. Our view of him depends on how he is to be understood as a monarch and as a man. The auburn headed teenager with a slight speech impediment who faced down the peasants at Smithfield was certainly courageous. The fact that the peasants followed him may have convinced him of his appeal as a sacral figure.

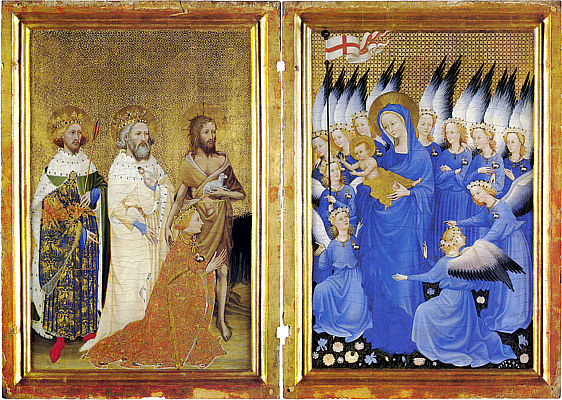

Richard sought the security of his position and his realm. Sanctification of both was his aim if we read correctly the implications of the Wilton Diptych, probably painted in 1397. Later in his reign he saw himself as the defender of religious orthodoxy.

What were Richard’s motivations in 1381 and what was his attitude to his subjects, high or low, whether rich or poor, powerful or powerless? Some historians have posited that he had ‘sympathy’ for the peasants. A more likely view is that he saw all his subjects as just that, and if they misbehaved it was his duty to bring them back into line. He was to find out within a few years that some of his relatives and nobles did not accept that view.

Was Richard misled by the peasants response to him at Smithfield? It may have confirmed his sense of regal invincibility. Should modern politicians be careful of the equivalent dangerous trap and was Richard in a ‘Westminster bubble’?

Chief Justice Cavendish had been lynched by rebel peasants near his Suffolk home in 1381. His successor fared worse. Richard’s questions about the extent of his prerogative powers to the judges at Nottingham Castle in 1387 helped precipitate the attack upon the King’s Court faction, including those judges, by the Appellants in the Merciless Parliament of the following year. Today there is considerable talk about the politicisation of the judiciary and the decisions handed down in judicial reviews. Unlike Chief Justice Tresilian in 1388 Lady Hale avoided being strung up at Tyburn at the behest of angry Brexiteers, or the fate of the rest of the bench, who were exiled to Ireland.

Other casualties of 1388 were several of the King’s Chamber knights, men attendant upon him who were the special advisors of their day.

Although Richard II sought peace with France he failed to achieve a settlement of the issues over his Duchy of Aquitaine. His pursuit of a deal with the French helped sour relations with some of the political leadership at home. He would not one suspects be favourable to the equivalent of Brexit - in his last years he appears to have considered seeking election as the prospective Holy Roman Emperor, an office held previously by his first wife’s father and brother.

Richard II and his 20x cousin Elizabeth II might share the view that troublesome relatives do sometimes have to be exiled or encouraged into self-imposed exile, although Her Majesty has not gone so far as to having an uncle smothered.

In the film “Kind Hearts and Coronets” the Rev. Lord Henry D’Ascoyne opines that the west window of his church has “all the exuberance of the age of Chaucer and none of the concomitant vulgarity.” The rededication of England as the Dowry of Mary links us again to that same age. We may ponder just how exuberant and just how vulgar we are today.

The Wilton Diptych - King Richard II kneels before Our Lady and the Christ Child

Image:reedDesign

No comments:

Post a Comment