If buildings could be destroyed so thoroughly as I indicated in my previous post on this thread then furnishings stood even less chance, although being portable they were carried off and individual examples do survive. However given that English iconoclasm was so often directed against the images and paraphanalia of Catholic worship the survivals are a miniscule percentage.

The examples I give of survivals are one which my mind or a bit of research turned up - this is in no way an attempt to include all examples, or to assess survival rates. What hopefully this will indicate are the sometimes extraordinary lengths people went to to save what they considered inportant, and also just how much has been lost.

If many medieval paintings were on the walls of churches then they disappeared under whitewash or went down as the building was destroyed.

The Doom painting in the church of St Thomas Salisbury

The painting is dated to about 1475 and is the largest to survive in England.

The figures at either side are thought to be St James, patron of pilgrims and St Osmund, the first bishop of Salisbury. The painting was rediscoverd and restored in the nineteenth century

Image and text (clightly adapted): Aidan Macrae Thomson on Flickr

In Nottingham Castle Museum are three fine atnding figures in alabaster which were found under teh floor of the demolished church at Flawford in Nottingham shire in 1779. They depict Our Lady, St Peter and a bishop. There is more about the history of the church and figures here.

The Doom painting in the church of St Thomas Salisbury

The painting is dated to about 1475 and is the largest to survive in England.

The figures at either side are thought to be St James, patron of pilgrims and St Osmund, the first bishop of Salisbury. The painting was rediscoverd and restored in the nineteenth century

Image: martinstown.co.uk

There is more about the painting at The Medieval Doom Painting in St. Thomas's Church Salisbury

The two greatest surviving British devotional panel paintings of the late middle ages may well have survived because they included royal portraits. Thus in addition to the great Westminster portrait of King Richard II we still have the wonderous Wilton Diptych - but before it was engraved by Wenceslaus Hollar in the 1630s its history is unknown.

The Wilton Diptych

Image: Wikipedia

From Scotland there are the equally fine Trinity panels by Hugo van der Goes from Edinburgh, dating to the late 1470s or early 1480s:

The Trinity Panels

Image:Wikipedia

These almost certainly survived because they include portraits of King James III and his Queen Margaret, but how they went from the Trinity collegiate church to first be recorded in the 1617 inventory of paintings at Oatlands of Queen Anne, wife of King James VI and I is similarly unrecorded.

Jon Cannon gives three good exampes of ecclesiastical re-cycling of stonework on his Extollogy! blog:

The first is the pulpitum bought by the merchant Thomas White

from the dissolved Carthusian friary in Bristol and presented in 1542

to the city’s new cathedral - itself a building re-cycled from being St Augustine's abbey. This massive screen, almost a small

building, is decorated with his merchant’s mark and the coats of arms of

King Henry VIII and Prince Edward, and emphatically a fitting needed for a

church in which the offices were to be sung in an exclusive enclosure

rather than one which de-emphasised priesthood and emphasised

congregational participation. It served as the entrance to the choir of Bristol for three hundred years, when the nave was rebuilt and the cathedral re-ordered. Fragments of it survive.

He gives two more circumstantial examples. The famous shrine base of St

Edburga, rescued by persons unknown from Bicester priory and installed on

the north side of the chancel at Stanton Harcourt, also in Oxfordshire, where it was

placed on top of a crudely carved platform covered in Christological

imagery. It has been suggested the parishioners intended to use it as an

Easter sepulchre, an idea endorsed by Cannon. In a decade or so, such dramatic

church furnishings would be abandoned with the liturgical cahnges of 1549 and 1552.

His third example are the palatial sedilia at Wymondham Abbey in Norfolk. Like the

pulpitum and the Easter Sepulchre, such fittings embody traditional

faith, emphasising as they do the status of the priesthood . Cannon says that surely this sedilia, itself a very late creation -

going on style alone, of the 1510s at the earliest, and the 1520s seems

more likely - was originally on the south side of the high altar at the

abbey. Presumably, once again, the parishioners moved it here on the

assumption (perhaps a defensive assumption, perhaps not) that though the

abbey was no longer a going concern, and the choir unroofed, their continuing use of the nave as the parish church meant that it required, or could certainly use a sedilia His photograph shows how it has been fitted into one of the Norman nave arcades.

Images: Extollagy! by Jon Cannon

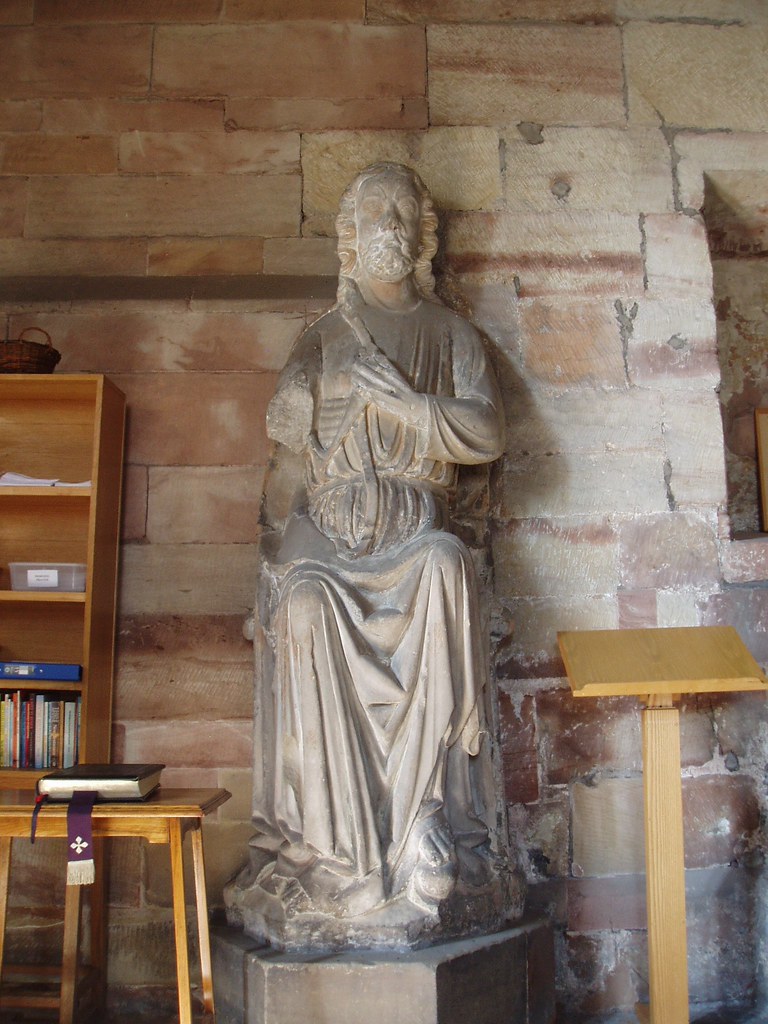

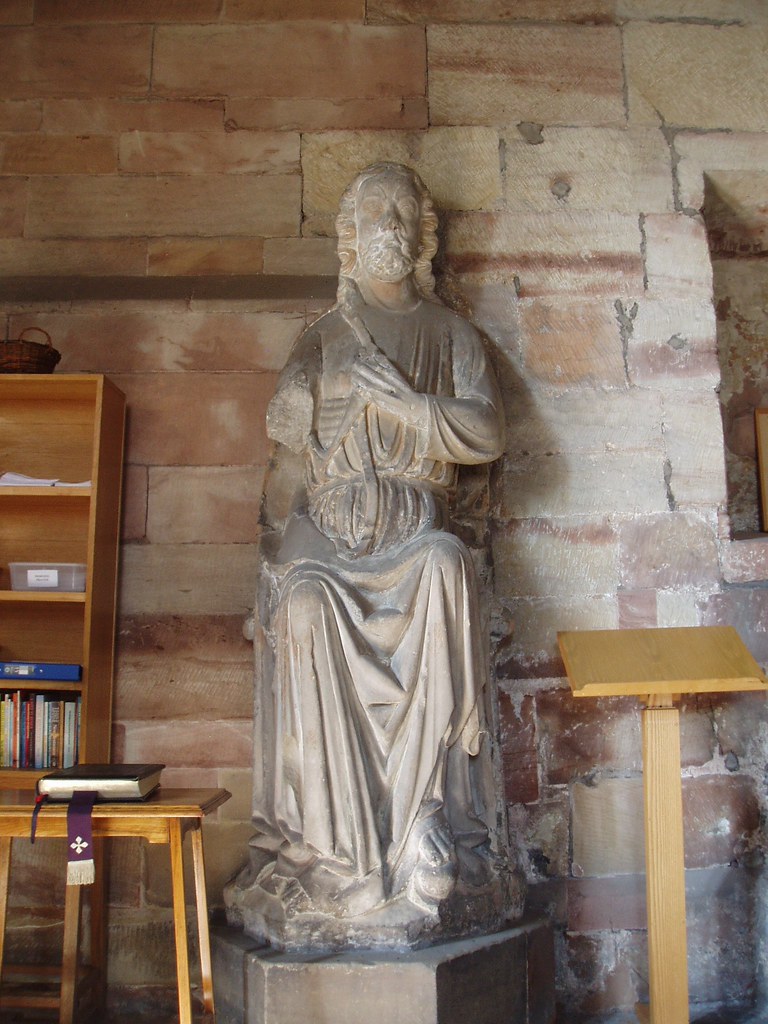

An even more remarkable survival, and one taht is surprisinly little known, is the Christ of Swynnerton in Staffordshire:

Seated Christ figure from the 13th century in

the south chapel (now used as a vestry)

St Mary's, Swynnerton,

Staffordshire.

The figure (approx 7'6'' in height) was unearthed under the floor close to where it now stands

in the 1800s, but clearly is far too large to have been made for this

church, and appears to have been designed to be viewed from below.

Clearly it was brought from elsewhere presumably at some

post-Reformation point, but from where, and why?

Firstly the church's website must be ignored, as it suggests a theory

that the figure was brought here from Reims, an error that seems to

derive from a very literal misreading of Pevsner's comment on certain

stylistic influences in the carving (he mentions a 'slightly feline

look about the eyes (Reims is the origin)' which refers to the style,

not the literal provenance of the statue!). This is very much an

English sculpture produced in the mid-thirteenth century which

otherwise bears far more comparison with contemporary work at Wells

and York than Northern France!

Secondly the stone is very much the local sandstone of this part of

the Midlands, making Staffordshire itself as likely an origin as

anywhere. But how many buildings within reach of Swynnerton would have

been large enough for such a figure, presumably set in a high niche on

a facade?

Only one candidate seems to make sense, Lichfield Cathedral, as it

fulfils several criteria; prior to the Civil War (and the grevious

damage inficted by it) Lichfield's west front retained it's complete

array of thirteenth century sculpture, including a figure of Christ

like this one in the gable, as can be seen in Wencesllas Hollar's

engraving from the 1630s. Most of the figures were lost in the

subsequent conflictt (except a row of kings and some battered figures

around the central portal, all thoroughly restored and eventually

completely replaced in Gilbert Scott's 'renewal' of the facade. About

four figures alone survive today high up on the north tower). The

stone is also a match for the cathedral.

The main problem is the considerable distance from Lichfield; it seems

safe to presume the statue was buried here to protect it from puritan

iconoclasts, but why Swynnerton and not some spot closer to 'home'?

The most significant connection of this locality to Lichfield could be

the presence nearby of Eccleshall Castle, which was then the private

residence of the Bishops of Lichfield, and would have proved a welcome

retreat for the clergy whilst Lichfield was under siege (on more than

one occaision). Was this figure spirited away from the cathedral after

the first siege had damaged it (worse was inflicted during the

second)? We will probably never know for certain.

All we know for certain is that Lichfield possessed a figure of the

same size and date as this one, which disappeared at some point during

the Civil War and was presumed destroyed. A figure of King Charles II

replaced it at the Restoration, to be in turn replaced by Scott with

the Christ we see on the gable today. (The statue of King Charles II now stands at ground

level at Lichfield and is a reasonable height match for this figure -

did they once both occupy the same niche?)

This theory was mainly supported by Arthur Mee in The King's England

Staffordshire (not the most reliable source!), but later Gerald Cobb in his

excellent English Cathedrals - the Forgotten Centuries 1984. It

seems somewhat under-recognised today.

There is however an alledged link with the local recusant Catholic

family, the Fitzherberts who worshipped in this chapel and are

believed to have place the figure in safety here. Dom Bede Camm in his

book 'Forgotten Shrines' relates the story at the following excerpt given here.

Alternatively to that we can only assume perhaps a large monastic

building in the area could have also hidden a Christ figure during the

Reformation, and brought it to safety at Swynnerton.

The statue is in good condition and not greatly effected by

weathering (a niche would have afforded some shelter). Traces of red

paint are visible within the sleeve of Christ's gown, proving that the

figure was once, like most medieval sculpture, painted in bright

colours.

Sadly this part of the church is closed off and generally inaccessible

to the ordinary public without prior arrangement. A great pity as it

is little known and one of the rarest and most significant English

works of its date.

Image and text (clightly adapted): Aidan Macrae Thomson on Flickr

In Nottingham Castle Museum are three fine atnding figures in alabaster which were found under teh floor of the demolished church at Flawford in Nottingham shire in 1779. They depict Our Lady, St Peter and a bishop. There is more about the history of the church and figures here.

To be continued

Great article, cant wait for more

ReplyDelete