202 years ago on February 14th 1820 the Duc de Berry, the third in line to the crown of France, died as a result of being stabbed the previous evening as he left the Opera in Paris.

The particular significance of the assassination of the 42 year old Duc was that if the child with which his wife was pregnant was a son then he would ensure at least another generation of the Bourbon succession, whereas a daughter would mean the throne passing to the suspect figure of Louis Philippe Duc de Orleans. The birth of a son to the widowed Duchesse de Berry later that year was seen, rather like that of King Louis XIV in 1638 as miracloud, and that the child was Dieudonné. Unfortunately the Comte de Chambord, the de jure King Henri V was never to reign in France, and with his death, childless, in 1883 the claim to the succession passed to the descendants of Louis Philippe in the person of the claimant King Philippe VII and to his descendants.

The Duc de Berry appears to have taken in appearance after his father, the later King Charles X, as a young man but in his later years came to resemble his uncle King Louis XVI.

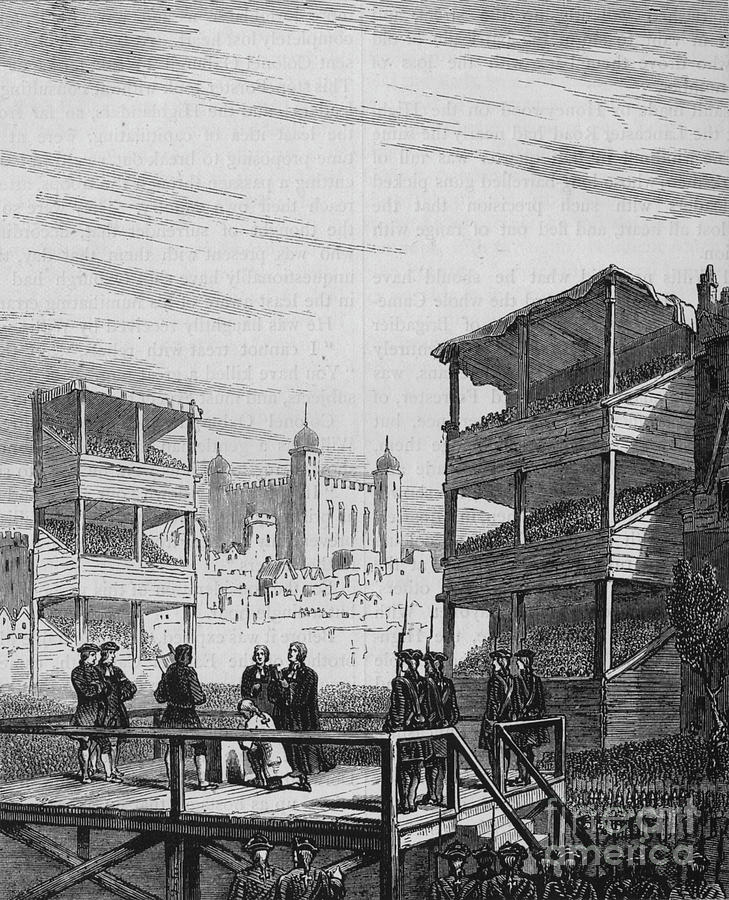

The Duc de Berry circa 1796

Image:Wikipedia

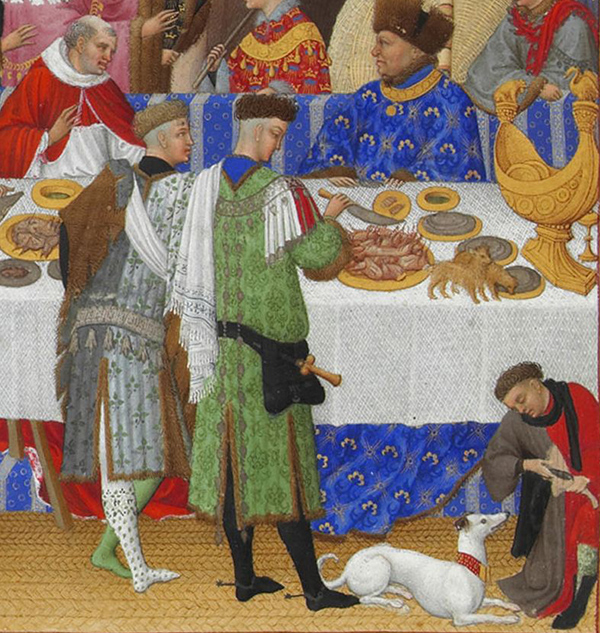

The Duc de Berry in his later years

He is wearing the riband and star of the Order of the Saints Esprit, the Order of the Golden Fleece, and what appear to be the Orders of St Louis and the Royalist Legion d’Honneur on his medal bar

Image: Wikipedia

The concern about leaving s legitimate heir in the person of the future claimant King Henri V is slightly amusing when one looks at the Duc de Berry’s, shall we say, track record. From his days in exile he had produced a series of illegitimate offspring with English and Scottish mistresses , and later with French ones after the Restoration. He has as a consequence many descendents today as indicated by the Wikipedia links. These include Mme. Giscard d’Estaing, widow of the former President, and Hervé Charette, a minister in the Chirac government. When the Duc was murdered in 1820 it was not just his wife that he left pregnant but three other women bearing his unborn children …. Very French.

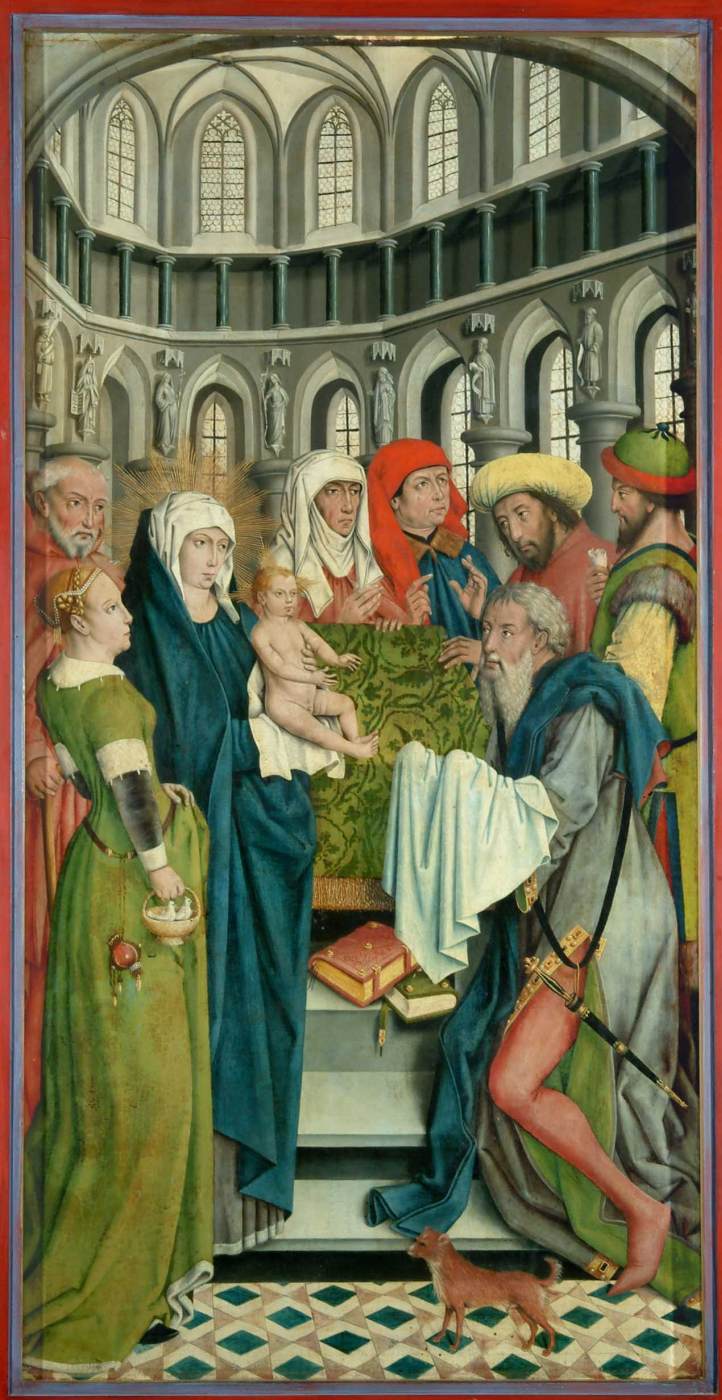

The Duc de Berry in state dress

Portrait by Francçois Gérard

The bust in the background is of King Henri IV

Image: Wikipedia