Sunday, 31 January 2021

Burying the Alleluia

A fragment of the Harry Crown?

The Oxford Almanack

Saturday, 30 January 2021

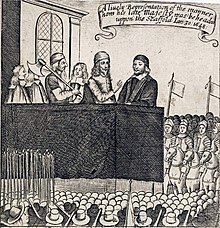

The remembrance of King Charles I

The Last Speech of King Charles I

I shall be very little heard of anybody here, I shall therefore speak a word unto you here.

Indeed I could hold my peace very well, if I did not think that holding my peace would make some men think that I did submit to the guilt as well as to the punishment. But I think it is my duty to God first and to my country for to clear myself both as an honest man and a good King, and a good Christian.

I shall begin first with my innocence.

In truth I think it not very needful for me to insist long upon this, for all the world knows that I never did begin a War with the two Houses of Parliament. And I call God to witness, to whom I must shortly make an account, that I never did intend for to encroach upon their privileges. They began upon me, it is the Militia they began upon, they confessed that the Militia was mine, but they thought it fit for to have it from me. And, to be short, if any body will look to the dates of Commissions, of their commissions and mine, and likewise to the Declarations, will see clearly that they began these unhappy troubles, not I. So that as the guilt of these enormous crimes that are laid against me I hope in God that God will clear me of it.

I will not, I am in charity, God forbid that I should lay it upon the two Houses of Parliament. There is no necessity of either. I hope that they are free of this guilt, for I do believe that ill instruments between them and me has been the chief cause of all this bloodshed; so that by way of speaking, as I find myself clear of this, I hope and pray God that they may too; yet for all this, God forbid that I should be so ill a Christian as not to say that Gods Judgments are just upon me.

Many times He does pay justice by an unjust sentence, that is ordinary. I will only say this, that an unjust sentence that I suffered to take effect*, is punished now by an unjust sentence upon me. That is, so far as I have said, to show you that I am an innocent man.

Now to show you that I am a good Christian; I hope there is [pointing to D. Juxon] a good man that will bear me witness that I have forgiven all the world, and even those in particular that have been the chief causers of my death. Who they are, God knows, I do not desire to know, God forgive them. But this is not all, my charity must go further.

I wish that they may repent, for indeed they have committed a great sin in that particular. I pray God, with St. Stephen, that this be not laid to their charge. Nay, not only so, but that they may take the right way to the peace of the kingdom, for my charity commands me not only to forgive particular men, but my charity commands me to endeavor to the last gasp the peace of the kingdom.

So, Sirs, I do wish with all my soul, and I do hope there is some here [turning to some gentlemen that wrote] that will carry it further, that they may endeavor the peace of the kingdom.

Now, sirs, I must show you both how you are out of the way and will put you in a way.

First, you are out of the way, for certainly all the way you have ever had yet, as I could find by anything, is by way of conquest. Certainly this is an ill way, for Conquest, sirs, in my opinion, is never just, except that there be a good just cause, either for matter of wrong or just title. And then if you go beyond it, the first quarrel that you have to it, that makes it unjust at the end that was just at the first. But if it be only matter of conquest, there is a great robbery, as a pirate said to Alexander the Great, that he was the great robber, he was just a petty robber. And so, sirs, I do think the way that you are in, is much out of the way.

Now, sirs, to put you in the way, believe it, you will never do right, nor God will never prosper you, until you give God his due, the King his due (that is, my successors) and the people their due. I am as much for them as any of you.

You must give God his due by regulating rightly His church according to the Scripture, which is now out of order. For to set you in a way particularly, now I cannot, but only this. A national synod freely called, freely debating among themselves, must settle this, when that every opinion is freely and clearly heard.

For the King, indeed I will not, [then turning to a gentlemen that touched the axe] Hurt not the Axe that may hurt me.

For the King the Laws of the land will clearly instruct you for that; therefore, because it concerns my own particular, I only give you a touch of it.

For the people, and truly I desire their liberty and freedom as much as any body whomsoever. But I must tell you that their liberty and freedom consists in having of government those Laws by which their life and their goods may be most their own. It is not for having share in government, sirs. That is nothing pertaining to them. A subject and a sovereign are clean different things, and therefore until they do that, I mean, that you do put the people in that liberty as I say, certainly they will never enjoy themselves.

Sirs, it was for this that now I am come here. If I would have given way to an arbitrary way, for to have all laws changed according to the power of the sword, I needed not to have come here. And therefore I tell you, and I pray God it be not laid to your charge, that I am the martyr of the people.

In truth, sirs, I shall not hold you much longer, for I will only say thus to you. That in truth I could have desired some little time longer, because I would have put then that I have said in a little more order, and a little better digested than I have done. And, therefore, I hope that you will excuse me.

I have delivered my conscience. I pray God, that you do take those courses that are best for the good of the kingdom and your own salvation.

[William Juxon, Bishop of London :]

Will Your Majesty, though it may be very well known Your Majesties affections to religion, yet it may be expected, that You should, say somewhat for the world's satisfaction.

[King:]

I thank you very heartily, my Lord, for that. I had almost forgotten it.

In truth, sirs, my conscience in religion, I think, is very well known to all the world. And therefore, I declare before you all that I die a Christian, according to the profession of the Church of England, as I found it left me by my father.

And this honest man [pointing to Juxon] I think will witness it.

[Then turning to the Officers]

Sirs, excuse me for this same. I have a good Cause, and I have a gracious God. I will say no more.

[Then turning to Colonel Hacker]

Take care that they do not put me to pain. And sir, this, and it please you...

[But then a gentleman coming near the Axe, the King said]

Take heed of the axe, pray, take heed of the axe

[Then to the Executioner]

I shall say but very short prayers, and when I thrust out my hands.

[Then the King called to Juxon for His night cap and put it on. Then to the Executioner]

Does my hair trouble you?

[The Executioner desired Him to put it all under His cap, which the King did accordingly, by the help of the Executioner and the Bishop. Then the King turning to Juxon:]

I have a good cause, and a gracious God on my side.

[Juxon:]

There is but one Stage more, which is turbulent and troublesome, yet it is a short one. You may consider it will soon carry you a very great way. It will carry you from earth to heaven. And there you shall find a great deal of cordial, joy, and comfort.

[King:]

I go from a corruptible, to an incorruptible Crown, where no disturbance can be, no disturbance in the world.

[Juxon:]

You are exchanged from a temporal to an eternal crown. A good exchange.

[The King then asked the Executioner]

Is my hair well?

[Then the King took off his cloak and his George, giving his George to Juxon, saying:]

Remember.

[Then the King put off his doublet and, being in his waistcoat, put his cloak on again. Then looking upon the block, the King said to the Executioner:]

You must set it fast.

[Executioner:]

It is fast, sir.

[King:]

It might have been a little higher.

[Executioner:]

It can be no higher, sir.

[King:]

When I put out my hands this way, then.

[After having said a few words as he stood to himself with hands and eyes lift up, immediately stooping down, the King laid his neck on the block. Then the Executioner again putting his hair under his cap, the King said:]

Stay for the sign.

[Executioner:]

Yes, I will, and it please Your Majesty.

[After a very little pause, the King stretching forth his hands, the Executioner at one blow, severed his head from his body.]

* The King is referring to the execution of the Earl of Strafford in 1641

Wikipedia has a useful and detailed account of the events of January 30th 1649 and of the varied historiographical interpretations of the King’s death which can be read at Execution of Charles I

Image: History Today

In his speech the King maintains the case he had made at the trial in Westminster Hall as to maintaining the historic constitution, the Church of England and the rights of his subjects against the militant clique who had seized power and brought about his death. It includes two of his sayings that are often quoted, about the absolute difference between sovereign and subject and about his exchanging his corruptible crown for an incorruptible one. He spoke also of his successors as monarchs - he clearly did not see his death, or wish to imply it as signifying the end of the institution he still embodied.

Given the circumstances under which it was given it is a recollected and balanced defence of his rights and actions. It conveys a sense of resignation to his fate but also a calm reassertion of his view of kingship and a belief in its ultimate vindication. It is in some ways prophetic of the events of the coming eleven years and of the Restoration, when Bishop Juxon, who noted down the speech in shorthand, newly promoted to the Archbishopric of Canterbury was to crown King Charles II.

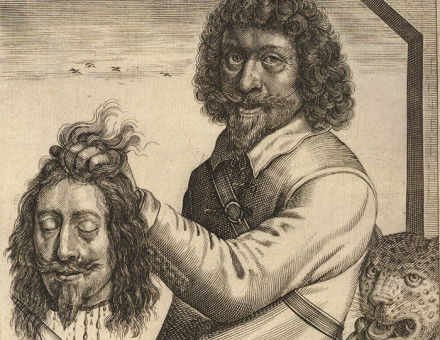

The Apotheosis, or, Death of the King is a 1728 line engraving by French engraver Bernard Baron (1696-1762). It reflects the then still dominant Anglican view of King Charles I as Christian martyr. In the foreground, the King is taken to Heaven by a group of angels while Britannia looks down in shame. In the background the execution has taken place and the crowd is in an uproar.

Friday, 29 January 2021

The fabric of Solomon in all his glory

Kaiser Wilhelm II and his Garter Insignia

Thursday, 28 January 2021

The language of Kings

It's generally believed that Henry IV was the first to speak English as his first language — that is, the language he learned first in infancy and spoke by preference. His son Henry V actuvely promoted English as a ‘national’ language and as one of record.

Many previous kings probably spoke at least some English. One of the comments from a reader suggests that Henry II might have been able to speak some English. Henry II probably wouldn’t have been fluet, but he spent large amounts of time hunting around England and probably would have picked up some English from the locals during his travels. We know that Richard II did, because there was the famous incident when as a teenager he spoke to the rioting crowd during the Peasants' Revolt. The three king Edwards are reputed to have understood spoken English, but not been fluent enough to speak it themselves. One commentator cited Edward II’s recorded predilection for the company of labourers as suggesting he could communicate easily enough with them in English. Another says that Edward III spoke some English with a variety of words and phrases to hand but not enough to be able to complete a sentence. Another adds that he had read that his son Edward, Prince of Wales spoke French to his Gascon troops and English to his English troops, and that having seen some of his written French, from the spelling, he seems to have spoke French with a London accent! Poitiers, for example is spelt Petters.

For the first hundred years after the Norman Conquest, French seems to have remained the sole language of the nobility, and also of the higher ranks of the Church and the law courts. Most noble families owned lands on both sides of the Channel, and high-ranking children from England would often be fostered with their relatives in Normandy or Anjou, where they would speak French.

By the later 12th century, though — the reigns of Henry II, Richard and John — it seems that bilingualism was becoming more and more common. Royalty and aristocracy spoke French to each other and English to their servants.

The loss of Normandy and Anjou to the King of France under John accelerated the move away from French. The English aristocracy no longer had estates in Normandy, and could no longer as easily send their children to be educated in what was now a foreign country. During the 13th century, it seems that at least the lower ranks of the gentry became English-speaking.

French remained the language of the elite for longer, however. The Scottish chronicler John of Fordun, who wrote in Latin, sometimes quotes king Edward I Longshanks speaking in French, and helpfully provides a translation of his words into Latin for the benefit of his readers.

"Ne avoms ren autres chose a fer, que a vous reams a ganere?" Quod est dicere: "Nunquid non aliud habemus facere, quam tibi regna lucrari?"

(Roughly, "Do we have nothing better to do than win kingdoms for you?" 'Quod est dicere' is Latin for 'Which is to say'.)

By the 14th century, ambitious members of the English gentry were learning French because it was the prestige language: the language spoken by the king and his court. We have evidence of people paying for tuition, of language schools being set up, and even of textbooks being written explaining how to speak French.

This proves two things: that French was not, any longer, the mother tongue of at least the lower ranks of the English aristocracy: but that the ability to speak French fluently was considered essential for anyone who wished to enter polite society.

Robert of Gloucester, writing around the 1270s, had this to say:

so þat heiemen of þis lond, þat of hor blod come.

holdeþ alle þulk speche, þat hii of hom nome.

vor bote a man conne frenss, me telþ of him lute.

ac lowe men holdeþ to engliss, & to hor owe speche 3ute.So that high men of this land that of their [Norman] blood come

Hold to all that speech that they took from them;

For unless a man knows French, men think little of him.

But low men hold to English and to their own speech yet.

The monk Ranulf Higden, writing in the 1340s, was of a similar opinion:

Filii nobilium ab ipsis cunabulorum crepundiis ad Gallicum idioma informantur. Quibus profecto rurales homines assimilari volentes, ut per hoc spectabiliores videantur, francigenare satagunt omni nisu.

The children of nobles are taught the French language from the very cradles of infancy. People from the countryside, wishing to make themselves similar to them in order to appear more respectable, make every effort to learn to speak French.

In the 1380s the linguist and Oxford scholar John Trevisa, who among other things translated Ranulf Higden's work into English, suggested another reason for the continued prevalence of French: that it served as a lingua franca:

Hit seemeth a greet wonder how Englisshe, that is the birth-tongue of Englisshemen and her owne language and tonege, is so dyversse of soune in this oon iland, and the language of Normandie is comlyng of another londe, and hathe one manere soun among ale men that speketh hit aright in Engelond— Nevertheless, there is as many dyvrese manere Frensshe in the reem of Fraunce as is dyvers manere Englisshe in the reem of Engelond. For a man of Kent, Southern, Western and northern men speken Frenssche al lyke in soune and speche, but they can not speke theyr Englyssche so.

In other words, the many dialects of English spoken throughout England are often not intelligible to each other; but wherever you go in England, north, south or west, there will be people who will understand you if you speak the one standard dialect of Norman French.

However, Trevisa wrote in 1385 that knowledge of French in England appeared to be a lot less than in Higden's day two generations earlier. He dated this change specifically to before and after the Black Death. Before the plague, schools in England generally used French as their language of teaching, and moved onto Latin for more advanced students. In the second half of the 14th century, though, students were arriving in school with little knowledge of French, and the instruction was largely provided in English.

The French poet Froissart attended the court of King Richard II and was surprised to find the nobles there speaking in English to each other: he'd expected they would speak French. However, when he read out extracts from his work for the king in French, the King understood him and praised his work in the same language. Meanwhile in England Geoffrey Chaucer, who could read both Latin and French fluently, nevertheless chose to write his poetry in English in order to reach a wider audience.

It seems then that it was roughly the years 1350-1420 that marked the transition between French being the regularly-spoken language of the upper classes (even if they also understood English as well) to it being entirely a second language learned in school.

The Clever Boy would add that his long held view is that this is not a matter of

‘either/or’ but rather that Kings and nobles, and indeed the literate classes generally, would have had one language that they were most comfortable in - French, then English - plus English and subsequently French as a second language to talk to servants in the first case and visitors in the second as time moved on - plus some Latin for church use, legal matters and international dealings, as well as for devotional, scholarly and recreational reading.