I know I am a bit odd but when I hear of MPs wanting troops sent to Calais or see newspaper headlines such as "Army ready to act over Calais crisis" I begin to wonder if I, or the media, have time-travelled back to 1436, when Duke Humphrey saved the day, or 1558, when we lost Calais to the French after 211 years.

Are we going to liberate the town and Pale so that it can once more send, as it did from 1540 until 1558 two MPs to Westminster? Has we retained that bridgehead on the continent our view of Europe might well be somewhat different. It could be our Ceuta or Mellila.

Could this be for the government what the Crimea has been for Vladimir Putin?

Friday, 31 July 2015

St Neot

July 31st is the feast, inter alia, of St Neot.

By way of introduction I will reproduce this piece about the church of St Neot in Cornwall from Wikipedia:

The original dedication may have been to 'St Anietus', with whom the

Saxon Neot has been confused. In the 11th century a small monastery

existed here; the early medieval church building (of which the tower

remains) must have been smaller than the one in existence today.

Rebuilding in granite was undertaken in the 15th century and the fine

stained glass windows are from about 1500. The stained glass is partly original and partly from a restoration done by John Hedgeland, circa 1830.

There are 16 windows of 15th or 16th century workmanship unless

indicated: 1: the Creation window; 2: the Noah window; 3: the Borlase

window; 4: the Martyn window; 5: the Motton window; 6: the Callawy

window; 7: the Tubbe and Callawy window; 8: an armorial window

(Hedgeland); 9: the St George window (15th century); 10: the St Neot

window (12 episodes from the legend); 11: the Young Women's window (four

saints with the 20 donors below); 12: the Wives' window (Christ and

three saints with the 20 donors below); 13: the Harris window; 14: the

Redemption window (Hedgeland); 15: the Acts window (Hedgeland); 16: the

chancel window depicts the Last Supper (Hedgeland; copied from the

earliest representation in the British Museum).

Nearby is the holy well of St Neot. Legend tells that the well

contained three fish, and an angel told St Neot that as long as he ate no

more than one fish a day, their number would never decrease. At a time

St Neot fell ill, and his servant went and cooked two of the fish; upon

finding this, St Neot prayed for forgiveness and ordered that the fish

be returned to the well. As they entered the water, both were

miraculously returned to life.

There is another piece about the church from the Cornwall Historic Churches Trust at www.chct.info/histories/st-neot/ This makes the point that after Fairford in Gloucestershire this is the most complete schenme of late medieval glazing to survive. |

St Neot Parish Church, Cornwall

Image:© David Coppin

Image:© David Coppin

Gordon Plumb has posted the following piece on the Medieval Religion discussion group, which I have copied in its entirety and which looks at the cult of the saint and its depiction in stained glass

St Neot, St Neot, Cornwall, nVII:

Glass of c1530 showing the story of St Neot. Neot was a monk and hermit who gave his name to St Neot, Cornwall and St Neots, Cambridgeshire (formerly Hunts). He joined the Glastonbury community early in his life and moved from there to a spot near Bodmin Moor as a hermit, and there he founded a small monastery. He was buried in the church where, later, his relics were enshrined on the north side of the sanctuary.

In 972-7 Earl Leofric founded a monastery at Eynesbury in Huntingdonshire with monks from Thorney abbey. These monks obtained by gift or theft the greater part of the relics of Neot from the Cornish shrine. That is what the accepted medieval version of Neot's life says, but G. McNeil Rushforth in his article on the St Neot's glass says "It is a far cry from Huntingdonshire to Cornwall, and it seems more probable that there were two distinct saints - a Saxon Neot, perhaps founder of St Neot's Priory in Huntingdonshire where he was buried, and a Celtic or Cornish Neot (whose real name may have been Aniet or Niet), founder of a monastery or college which existed till the Norman Conquest. About the end of the eleventh century the Norman Abbey of Bec acquired a cell at Cowick, near Exeter, and it is suggested that here the monks may have heard of the Cornish St. Neot and the stories about him. In an uncritical age it was not to difficult to identify the two Neots and then to suppose that the body of the saint had been brought to Huntingdonshire from Cornwall".

The town of Eynesbury was then called St Neots. The priory was refounded c1086 from Bec in Normandy. Anselm declared that its relics were authentic and complete except for an arm left in Cornwall. Anselm gave to Bec a relic of Neot's cheekbone, presumably from the shrine at Eynesbury.

Neot is claimed to be of royal blood - either the East Anglian or Wessex dynasties. According to the Oxford Dictionary of Saints he was so small that he needed a stool to stand on when saying mass! The life written at Bec, one of three Latin lives (plus one Old English life) related incidents borrowed from the lives of Irish saints - including that of stags being yoked to the plough to take the place of oxen stolen by robbers. This Bec life is the source of this window at St Neot, donated by the young men of the parish in ?1528 (the date is missing in records of the glass before restoration).

The window was subjected to considerable restoration by J.P.Hedgeland in the later 1820's who, according to one writer "supplied deficiencies in a manner so perfectly like the former, as not to be distinguishable from it"! Hedgeland did plates of the restored windows in a book published in 1830..

Here are details of the panels of the window and an indication of their subject matter

Panel 3a, Neot abdicates in favour of his brother, on whose head he places the crown:

Panel 3b, Neot becomes a monk at Glastonbury:

Panel 3c, Neot saves a doe from a hunter:

Panel 3d, Neot finds three fish in his well:

Panel 2a, Neot bids his attendant bring him the fish for his meal:

Panbel 2b, Neot's attendant takes two fish from the well, grilling one and boiling the other:

Panel 2c, attendant brings Neot two fish fo9r his daily meal:

Panel 2d, attendant takes two fish he has cooked back to well and throws them in as ordered by Neot, and they are restored to life:

Panel 1a, theft of Neot's oxen:

Panel 1b, deer replace the oxen in ploughing:

Panel 1c, The thieves restore the stolen oxen:

Panel 1d, Neot at Rome receiving the Pope's blessing.

Here is my photograph of the Hedgeland plate of the restored St Neot window, photographed from my copy of the book:

The glass of St Neot is discussed, other than in the 1830 book by Hedgeland by:

G[ordon] McN[eil] Rushforth, The Windows of the Church of St Neot Cornwall. Transactions of the Exeter Diocesan Architectural And Archaeological Society, Vol. XV, 1937. Later separately reprinted innthe same year as a 43pp. pamphlet

Mattingley, Joanna, "Stories in the Glass - Reconstructing the St Neot Pre-Reformation Glazing Scheme, Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, New Series II, Volume III, Parts 3 and 4, 2000, pp. 9-55.

The parish church of St Mary at St Neots in Huntingdonshire

Image:churchestogetherinstneots.org.uk

Wednesday, 29 July 2015

A fateful marriage

Today is the 450th anniversary of the marriage at Holyrood of Queen Mary I of Scots to Henry Lord Darnley, whom she had created Duke of Albany and who through his marriage became King Consort of Scots. There is a biography of him, illustrated with several portraits, at Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley

King Henry and Queen Mary

A painting of 1565, now at Hardwick Hall

Image: Wikimedia

The marriage potentially reinforced both their claims to the English throne as close relatives of Queen Elizabeth, and as Catholics, or at least sympathetic to Catholicism, likely to receive the support of conservative minded Englishmen in the event of the throne becoming vacant.

In reality the marriage was far from placid, with suspicion and the threat or reality of violence, such as the murder of Rizzio. Their one child, the future King James VI was born in June 1566, but in February 1567 King Henry was murdered at Kirk o Field, followed by the reaction against Quen Mary, her deposition and imprisonment and the passing of the crown to their son, who was crowned as King of Scots two years to the day after his parents wedding. The following year Queen Mary escaped from Loch Leven, was defeated and fled to England, and nineteen years of house detention before she died by the headsman's axe at Fotheringhay.

Is it to indulge in superstition to reflect in passing that the only other royal wedding held on July 29th was that in 1981 of the Prince of Wales and Lady Diana Spencer? Furthermore the only previous royal nuptials celebrated in St Paul's were those of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon in 1501 - and think what that led to. These were not good omens.

In reality the marriage was far from placid, with suspicion and the threat or reality of violence, such as the murder of Rizzio. Their one child, the future King James VI was born in June 1566, but in February 1567 King Henry was murdered at Kirk o Field, followed by the reaction against Quen Mary, her deposition and imprisonment and the passing of the crown to their son, who was crowned as King of Scots two years to the day after his parents wedding. The following year Queen Mary escaped from Loch Leven, was defeated and fled to England, and nineteen years of house detention before she died by the headsman's axe at Fotheringhay.

Is it to indulge in superstition to reflect in passing that the only other royal wedding held on July 29th was that in 1981 of the Prince of Wales and Lady Diana Spencer? Furthermore the only previous royal nuptials celebrated in St Paul's were those of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon in 1501 - and think what that led to. These were not good omens.

St Olaf's Day

Apart from being the feast of St Martha today is also the feast of St Olaf (Olav) of Norway, the patron saint of the realm and 'perpetual King of Norway.'

The detailed and informative Wikipedia article about him appears to have been updated and in its present form can be viewed at Olaf II of Norway

This is therefore a day upon which I remember and pray for my own Norwegian friends, and for the King and people of Norway.

May St Olav continue to intercede for them.

Tuesday, 28 July 2015

Oratorians commemorate St Philip Neri in Florence

A friend has very kindly sent me the link to a video of some of the celebrations last week in Florence to mark the 500th anniversary of the birth of St Philip Neri. These included the unveiling of a plaque on his birthplace, as can be seen in the clip by following the link at https://youtu.be/NWzfIwdg9y4

Monday, 27 July 2015

Death by drowning in sixteenth century England

Stephanie Mann at Supremacy and Survival: The English Reformation has linked to an article in the BBC History Magazine about the frequency of drowning as a cause of accidental death in the sixteenth century. The stories may be sad, but they are very human, and also give a fascinating insight into daily life, not to mention its hazards, in the period. Her post can be read at One Drowning Victim Among Many: Robert Parsons

More July Martyrs

Stephanie Mann's blog Supremacy and Survival: The English Reformation has recently had a series of posts on martyred priests and laymen - some of them convert Anglican clergy - from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century whose commemorations fall at this time of year. Her posts can be read at

YET Another Martyrdom in July: Blessed George Swallowell, Layman

Another Martyr in July: Blessed John Ingram

More Martyrs in July: Blessed Edward Thwing and Blessed Robert Nutter

Another Martyr in July: Blessed William Ward (William Webster)

Another Late July Martyr: Blessed Robert Sutton (and His Brother)

Not only are these stories of courageous men but they also contain insights into life not only in the recusant community but that of the country at the time.

SS Joachim and Anne

Had yesterday not been a Sunday it would have been in the novus ordo the feast of SS Joachim and Anne. In the pre-1970 ordo and in the Extraordinary Form it is the feast of St Anne, with St Joachim having his separate feast day on August 16th.

Gordon Plumb has posted a set of pictures of pre-reformation stained glass depictions of the couple and their daughter on the Medieval Religion discussion group. These serve, inter alia, to show aspects of devotion to Our Lady and her life in medieval England, and, by implication and extension, its extent. The frequent depiction of St Anne teaching the Virgin to read, and that the Virgin is often shown reading in depictions of the Annunciation does raise interesting points about the extent and expectation of female literacy in the period.

York Minster, sXXXV, 2b, the meeting at the Golden Gate:

York Minster, sXXXV, 3b, Annunciation to Joachim in the Wilderness:

York Minster, sIX, 2a, Marriage of Joachim and Anne:

York Minster, sIX, 1b, Birth of BVM:

Elland, St Mary the Virgin, West Yorks, east window, 3b, marriage, heavily restored:

Elland, St Mary the Virgin, east window, 2a, meeting at Golden Gate:

Thornhill, St Michael and All Angels, West Yorks, nIV, centre light:

Gresford, All Saints, Lady Chapel east, b3c, Golden Gate, very restored:

Gresford, All Saints,3d, very restored:

Gresford All Saints, same window, 2b, Presentation of Mary in Temple:

Great Malvern Priory, Worcs, NII, Golden Gate:

Norbury, St Mary & St Barlok, sVI, 2b-3b, Anne teaching Mary to read:

Wisbech, St Peter and St Paul, Cambs, sIX, teaching Mary to read:

Leicester, Jewry Wall Museum, roundel of birth of Virgin:

Stanford-on-Avon, St Nicholas, Northants, sIV, 1a, teaching the Virgin to read:

Nowton, Suffolk, Joachim and Anne on right:

York, All Saints North Street, east window, 2b-3b, teaching the Virgin to read:

Stamford, St George, sII, 2c, teaching the Virgin to read:

Exeter Cathedral, sIII:

Hingham, St Andrew, east window, St Anne and BVM:

Both Elland and Thornhill are not far from my home town. I regret to say I have never visited the church at Elland, but I have visited Thornhill, and the church is a treasure house of good things for the historic church-crawler. Not only is there this glass but Anglo-Saxon crosses and a splendid array of tombs of the Savile family. Very well worth seeing, and a church that deserves to be better known for it's contents.

Stanford-on-Avon and Gresford I have drawn attention to before. All Saints North Street in York is very well worth seeing - a lot of interesting late-medieval glass, including a depiction of a pair of spectacles of about 1410, and a charming interior re-designed or, if you prefer, restored, for Anglo-Catholic worship in the Sarum tradition more than a century ago.

Wisbech church I have not visited but it contains the remains of the last Marian bishops, such as Thomas Watson of Lincoln, and Abbot Feckenham of Westminster since they were detained in the Elizabethan period in Wisbech castle and buried in the parish church when they died.

Saturday, 25 July 2015

More images of St James

John Dillon posted a whole series of further images of St James the Great that are either late antique and medieval on the Medieval Religion discussion group site:

a) as depicted in the very late fifth- or early sixth-century mosaics (betw. 494 and 519) in the Cappella Arcivescovile at Ravenna:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/pelegrino/5779785736/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/pelegrino/5779785736/

b) as depicted (at center) in the earlier sixth-century mosaics (betw. 527 and 548) of the basilica di San Vitale in Ravenna:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/33563858@N00/5222652208

https://www.flickr.com/photos/33563858@N00/5222652208

c) as depicted (fourth from left) in the earlier to mid-sixth-century mosaics of the presbytery arch (carefully restored, 1890-1900) in the Basilica Eufrasiana in Poreč:

d) as portrayed in relief (at far left) on a leaf of the mid-tenth-century ivory Harbaville Triptych in the Musée du Louvre, Paris:

http://tinyurl.com/qdsovlz

http://tinyurl.com/qdsovlz

e) as depicted in the earlier eleventh-century mosaics (restored betw. 1953 and 1962) in the narthex of the katholikon of the monastery of Hosios Loukas near Distomo in Phokis:

f) as depicted (bottom register at far right; after St. Paul) in the mid-twelfth-century mosaics (c1143) of the chiesa di Santa Maria dell'Ammiraglio (a.k.a. chiesa della Martorana) in Palermo:

http://tinyurl.com/pohhre5 http://tinyurl.com/ouzt3ts

http://tinyurl.com/pohhre5 http://tinyurl.com/ouzt3ts

g) as depicted (lower register, center) in the mid-twelfth-century apse mosaics (completed in 1148) of the basilica cattedrale della Trasfigurazione in Cefalù:

h) as depicted in the later twelfth-century Ascension fresco (betw. 1176 and 1200) in St. George's Church, Staraya Ladoga (Leningrad oblast):

http://www.icon-art.info/hires.php?lng=en&type=11&id=1436

http://www.icon-art.info/hires.php?lng=en&type=11&id=1436

i) as portrayed in relief on the late twelfth-century portal (betw. 1190 and 1200) of the basilique primatiale Saint-Trophime at Arles:

http://tinyurl.com/3u59z6z http://tinyurl.com/orr4xql

http://tinyurl.com/3u59z6z http://tinyurl.com/orr4xql

j) as depicted (upper right, after St. Andrew) in the late twelfth- or very early thirteenth-century wooden altar frontal of Baltarga in the Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, Barcelona:

http://www.museunacional.cat/sites/default/files/015804-000.JPG

k) as portrayed in relief in an earlier thirteenth-century enameled copper repoussé plaque of Limousin origin (ca. 1220-1230) from the high altar of the abbey church of Grandmont, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York:

l) as portrayed in relief on the mid-thirteenth-century châsse of St. Eleutherius in the cathedral of Tournai/Doornik:

m) as depicted in the mid-thirteenth-century Touke Psalter from Bruges (ca. 1250-1260; Baltimore, Walters Art Gallery, Walters ms. W.36, fol. 50r):

n) as depicted (at left; at right, St. Peter) in a thirteenth-century fresco in Matera's rupestrian church of San Giovanni in Monterrone:

http://www.wikimatera.it/home/operation/foto/2792.jpg

https://c2.staticflickr.com/8/7386/9934235046_cb756af24b_b.jpg

http://www.wikimatera.it/home/operation/foto/2792.jpg

https://c2.staticflickr.com/8/7386/9934235046_cb756af24b_b.jpg

o) as depicted in a later thirteenth-century fresco in the circle of the apostles on the ceiling of the baptistery of Parma:

http://www.cattedrale.parma.it/Img/voltabatt/61-giacomoM_Z.jpg

p) as depicted in the late thirteenth-century Livre d'images de Madame Marie (ca. 1285-1290; Paris, BnF, ms. Nouvelle acquisition française 16251, fol. 66r):

q) as depicted (martyrdom; image greatly expandable) in a late thirteenth-century copy of French origin of Jacopo da Varazze's Legenda aurea (San Marino, CA, Huntington Library, ms. HM 3027, fol. 81v):

http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/ds/huntington/images//000944A.jpg

r) as depicted (martyrdom) in an earlier fourteenth-century copy (ca. 1301-1350), with illuminations attributed to the Fauvel Master, of a collection of French-language saint's lives (Paris, BnF, ms. Français 183, fol. 34v):

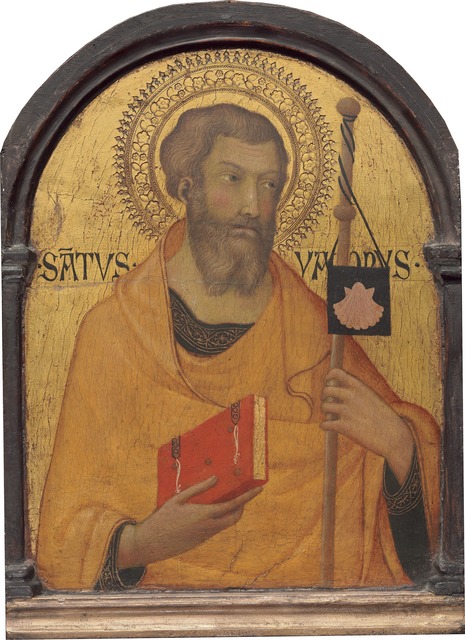

s) as depicted by the workshop of Simone Martini in an early fourteenth-century panel painting (ca. 1317-1320) in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC:

t) as depicted in an earlier fourteenth-century copy (1348) of the Legenda aurea in its French-language version by Jean de Vignay (Paris, BnF, ms. Français 241, fol. 169v):

u) as depicted in a mid-fourteenth-century panel painting (betw. 1355 and 1360) by Andrea di Vanni d'Andrea, now in the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples:

Detail view:

v) as portrayed in relief (third from right) on the late fourteenth- or early fifteenth-century tomb of St. Wendelin in his basilica in Sankt Wendel:

w) as portrayed in relief in a fifteenth-century English alabaster in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London:

x) as depicted by Martino da Verona (attrib.) in an early fifteenth-century fresco in the chiesa di San Giacomo del in Vago di Lavagno (VR) in the Veneto:

y) as depicted in an earlier fifteenth-century fresco (ca. 1440) in Ballerups kirke, Ballerup (Sjælland):

z) as depicted by Cosmè Tura in a later fifteenth-century panel painting (ca. 1475) from a dismembered altarpiece, now in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen:

aa) as portrayed in a later fifteenth-century limestone statue (betw. 1475 and 1500) of Burgundian origin in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York:

bb) as depicted (at upper left) on one of the wings (closed position) of Hans Memling's later fifteenth-century St. John Altarpiece (completed ca. 1479) in the Memlingmuseum, Sint-Janshospitaal, Bruges:

http://www.wga.hu/art/m/memling/2middle2/13john4.jpg

Detail view:

cc) as portrayed by Gil de Siloe in a late fifteenth-century alabaster statue (ca. 1489–1493) now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. In 1486, Isabel of Castile, patroness of the explorer Christopher

Columbus, commissioned an elaborate alabaster tomb for her parents, King Juan

II of Castile and his Queen Isabel of Portugal. This star-shaped tomb, still

standing in the center of the church of the Carthusian monastery of

Miraflores, outside Burgos, was made between 1489 and 1493 by Siloe, a sculptor thought to be of Netherlandish origin. This statuette

of the patron saint of Spain is known from old photographs to have been

originally placed near the head of the Queen.:

dd) as portrayed in a very late fifteenth- or very early sixteenth-century wooden statue from Hasslöv (Hallands län), now in the Historiska Museet in Stockholm:

http://www.kringla.nu/kringla/objekt?referens=shm/art/920826S2

http://medeltidbild.historiska.se/medeltidbild/mbbilder/bilder/92/9225217.jpg

http://medeltidbild.historiska.se/medeltidbild/mbbilder/bilder/92/9225217.jpg

ee) as portrayed (third from left) in the very late fifteenth- or very early sixteenth-century statues of the apostles (betw. 1498 and 1509) in the south porch of the chapelle St.-Herbot in Saint-Herbot, a locality of Plonévez-du-Faou (Finistère):

ff) as portrayed (seated) in an early sixteenth-century polychromed wooden statue (betw. 1501 and 1515) in the Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin:

St James the Great

Today is the feast day of St James the Great.

Here in the Thames Valley Reading Abbey was given a relic of him in form of one of his hands by the Empress Matilda. The Empress had brought this back to England after the death of her first husband the Holy Roman Emperor Henry V, and although it properly belonged to the Imperial collection she, her son King Henry Ii and the monks of Reading ensured it stayed in England. Today it is now preserved in the Catholic church in Marlow. I have posted about this previously in The Hand of St James and in More on the Holy Hand of Reading.

There is more about it in an illustrated post from a blogger here, and a piece about both the hand and other aspects of medieval English devotion to St James here.

Gordon Plumb has posted on the Medieval Religion discussion group site

more of his photographs of medieval stained glass images of St James the

Great:

Chartres, Cathédrale Notre Dame, Bay 5, St James window set of images:

Acaster Malbis. Holy Trinity, Yorkshire, east window, 3d-4d:

Barton upon Humber, St Peter, east window( ex, at present in storage with English Heritage in York awaiting conservation - which is where I photographed it):

and detail:

Oxford, Merton College Chapel, west window:

North Tuddenham, St Mary, Porch, Norfolk, porch, west window, 1b-3b:

detail:

York, St Mary Castlegate, sIII, 2b:

and detail:

York Minster, wI, 5f-7f, 1340's (right-hand figure):

Harpley, St Lawrence, Norfolk, wI, A4:

York, All Saints North Street, sVI, 2a-3a:

and detail:

Stamford, Browne's Hospital, sII, 9a-11a:

Icklingham, All Saints, Norfolk, sII, 2b (figure on right):

Langport, All Saints, Somerset, east window, c2:

Bourges, Cathédrale St Étienne, Bay 27 father and mother of Pierre Trousseau presented by St James the Great, :

Bourges, Cathédrale St Étienne, Bay 25, Annunciation with St James and St Catherine:

Tattershall, Holy Trinity, Lincolnshire, east window, 3b:

Gloucester Cathedral, east window (figure on left)

Doddiscombsleigh, St Michael, Devon, nIII, 2a:

and detail:

Friday, 24 July 2015

Saints of the day

When I happened to look at the Universalis list of saints of the day I was interested to see not only St Charbel from the General Calendar, but some other English and Irish saints as well, and thought the Universalis piece copying and adapting as follows:

| St Charbel Makhlouf (1828 - 1898) |

|---|

He was born in the Lebanon, the son of a mule-driver, and brought up by his uncle, who did not approve of his devotion to prayer and solitude. He would go secretly to the monastery of St Maron at Annaya, and eventually became a Maronite monk and was ordained priest. After being a monk for many years, he was drawn to a closer imitation of the Desert Fathers and became a hermit.

At his hermitage he lived a severely ascetic life with much prayer and fasting. He refused to touch money and considered himself the servant of anyone who came to stay in the three other cells that the hermitage possessed. He spent the last 23 years of his life there, and increasing numbers of people would come to receive his counsel or his blessing.

There is an online article about him here.

Saint Declan

|

|---|

He was an early Irish bishop and abbot. He is sometimes said to be one of four bishops to have preceded Saint Patrick in Ireland in the early 5th century (See also Saints Ailbhe, Ciaran, and Ibar), although he is also made a contemporary of Saint David in the mid-6th century. There is an online article about him here.

| Blessed Robert Ludlam and Nicholas Garlick (d. 1588) |

|---|

Robert Ludlam was born around 1551, in Derbyshire, the son of a yeoman. After studying at Oxford he went to the English College at Rheims and was ordained priest there in September 1581. At the end of April 1582 he set out for England to pursue his ministry there.

Nicholas Garlick was born around 1555, also in Derbyshire. He spend several years as a schoolmaster, then went to the English College and was ordained at the end of March 1582. He came to England in January 1583.

The Padley Martyrs

Image:supertradmum-etheldredasplace.blogspot.co.uk,

There is a biography of Nicholas Garlick at https://thecatholicchurchinglossop.wordpress.com/2012/04/17/blessed-nicholas-garlick/

Both Ludlam and Garlick were arrested at Padley Hall, in north Derbyshire, whose owner, Sir Thomas Fitzherbert was imprisoned in the Tower of London until his death in 1591.

At Padley the manor gatehouse with a small chapel, restored in 1933 is a pilgrimage site. There is an annual pilgrimage and an account of the chapel, and longer biographies of both the martyrs, can be found at the sections on the Diocese of Hallam's website History of Padley Chapel and A brief history of Padley Martyrs' Chapel and Manor

Padley Chapel

Image: peakdistrictonline

Close to the site of their execution is St Mary's Chapel Derby. There is an account of it at St Mary's Bridge Chapel

St Mary's Bridge Chapel, Derby

Image:derbyshire-peakdistrict.co.uk

The interior of the chapel

Image:derbyshire-peakdistrict.co.uk

It was the story of the Padley Martyrs that inspired Mgr. Robert Benson to write his work of historical fiction about the period.

St John Boste (c.1544-1594)

John Boste was born in Westmorland around 1544. He studied at Queen’s College, Oxford where he became a Fellow. He converted to Catholicism in 1576. He left England and was ordained a priest at Reims in 1581. He returned as an active missionary priest to northern England. He was betrayed to the authorities near Durham in 1593. Following his arrest he was taken to the Tower of London for interrogation. Returned to Durham he was condemned by the Assizes and hanged, drawn and quartered at nearby Dryburn on 24 July 1594. He denied that he was a traitor saying: “My function is to invade souls, not to meddle in temporal invasions”.

St John Boste

Image:supertradmum-etheldredasplace.blogspot.co.uk,

Stephanie A. Mann at Supremacy and Survival: The English Reformation has a post with more details of his life and death and that of another martyr whose anniversary fall probably today, Joseph Lambton, which can be seen at More Martyrs in July: Blessed Joseph Lambton and St. John Boste

Thursday, 23 July 2015

A new history of Syon Abbey

Given that today is the feast of St Bridget of Sweden I am not sure how providential or fortuitous it was that as I finished my voluntary shift this morning in the bookshop at the Oxford Oratory that I noticed on the shelves a copy of this new book by Professor Edward Jones about the great English Bridgettine monastery of Syon, and which is published by Gracewing at £9.99.

Image: Amazon

For those who do not know the story of Syon it can be summarised briefly as follows. In 1415 King Henry V - who was quite busy that year invading France - founded the only Bridgettine monastery in England. This was close to his palace at Sheen ( now Richmond) in Surrey and prospered until the reign of King Henry VIII. It was one of the mainsprings or wellsprings of late medieval English spirituality and devotion, influencing many members of the elite and beyond. The chaplain, St Richard Reynolds was one of the first martyrs of May 1535, and the house was dissolved four years later. Nothing daunted the Sisters went off to their family homes in groups and continued their common life. Returning to Syon in 1557 they were again dispersed in 1559, and left England with the retiring Spanish ambassador for Flanders. Forced by the Netherlandish revolt to seek refuge elsewhere they settled in Rouen until the victory of King Henri IV led this pro-Spanish community to seek refuge in Lisbon. There, always an English community in exile,they survived the Portuguese uprising against Spanish rule in 1640, the Earthquake of 1755, the Peninsular War, and desire some sisters leaving for England soon after the core community remained there until 1861 when they returned to England after more than three centuries. They settled first in Dorset and then Devon, latterly at South Brent. Tragically in recent decades the community has declined in numbers and they gave up their house in 2011 and now the two remaining sisters live the Bridgettine life within a home run by other religious in Plymouth.

Their archives are now at Exeter University where Prof Jones is based, and Exeter has made an important contribution to modern scholarship on this remarkable community.

From his book I discovered that one of the great treasures of Syon is now at the Catholic church at Heavitree near Exeter. This is one of the pinnacles from the original gatehouse at Syon, and presumably the one on which St Richard Reynolds head was impaled in 1535. This substantial relic has accompanied the sisters on their wanderings from Syon to Flanders, France, Portugal and back to England. They also, in token of ownership, retained the door key of the abbey buildings at Syon - the site now being occupied by Syon House, now the property of the Duke of Northumberland.

The book is handsomely illustrated and reflects academic research and the latest scholarship on the Order and the unique place of Syon on English Catholic history.

A book I am looking forward to reading at lenth and one which I would warmly recommend, and on a topic well worthy of study and reflection which I would also commend to anyone at all interested in the later medieval English Church, the reformation and in recusant history.

The one regret I have is that the book ends with the closure of the abbey, rather than its continuance and continuing prayer and witness.

May we join St Bridget in prayer for the sisters of Syon and all they represent.

Wednesday, 22 July 2015

The death of King Edgar

It was on July 8th 975 that there occurred the death of King Edgar. Allowing for the shift from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar in 1752 the exact anniversary can therefore be held to fall today.

Image: Wikipedia

The death of King Edgar 1040 years ago is important for two reasons.

His reign is important for his consolidation of what may well be described as an imperial kingship - something his uncle King Athelstan had developed in his reign between 924 and 939 as he expanded his realm - and most notably by his coronation in 973 at the abbey in Bath. This was fourteen years after his accession - though he may have had a coronation at that time - and took place when he had reached the age of ordination and took place on Whit Sunday. This was sacral kingship, celebrated in a Roman spa town, analogous to Charlemagne's Aachen. The Rite used in 973 remains the basis of the English Coronation ceremony, used most recently for the present Queen in 1953, 980 years later.

The King's subsequent visit to Chester where he was ceremonially rowed along the river Dee from the city to St John's church by several tributary kings became celebrated as an assertion and exemplification of English hegemony over Britain,

Described in the early twelfth century as having been "extremely small both in stature and bulk" by that, careful historian William of Malmesbury he was anything but slight in importance as a monarch and as a key figure in the development of the institution of the monarchy and of monasticism, exemplified in the Regularis Concordia of 973, to which there is an introduction here.

The sacrality of King Edgar's monarchy is recalled in this thirteenth century illumination in an anonymous Life of King Edward the Confessor

Cambridge University Library, MS Ee.3.59: fol. 3v

The King's subsequent visit to Chester where he was ceremonially rowed along the river Dee from the city to St John's church by several tributary kings became celebrated as an assertion and exemplification of English hegemony over Britain,

Described in the early twelfth century as having been "extremely small both in stature and bulk" by that, careful historian William of Malmesbury he was anything but slight in importance as a monarch and as a key figure in the development of the institution of the monarchy and of monasticism, exemplified in the Regularis Concordia of 973, to which there is an introduction here.

King Edgar seated between St Æthelwold and St Dunstan. From an eleventh-century manuscript of the Regularis Concordia

British Library, Cottonian MS Tiberius A III, f2v

Image: Wikipedia

There is an online account of his reign at Edgar the Peaceful, which has a bibliography of recent studies of the reign. The Oxford DNB life by Ann Williams can be accessed here and provides a more detailed and academic account.

The sacrality of King Edgar's monarchy is recalled in this thirteenth century illumination in an anonymous Life of King Edward the Confessor

Cambridge University Library, MS Ee.3.59: fol. 3v

Image: Wikipedia

The second reason for the significance of the death of King Edgar was that it brought about the accession of his elder son as King Edward, who was to go down in history as the Martyr, he appears to have been illegitimate or of doubtful legitimacy, and only a boy or teenager at the time. His murder three years later and replacement by his younger, legitimate half-brother King Æthelred II, seemingly with the involvement of the new king's mother, set in motion those elements of instability and lack of political legitimacy that were to haunt King Æthelred the Unready [Unraed signifying No Counsel, a pun on his name which means Good Counsel] and his reign.

There is an online account at of King Edward the Martyr at Edward the Martyr, and the Oxford DNB life, by Cyril Hart can be seen at Edward [St Edward; called Edward the Martyr] (c.962–978); this again provides a more detailed account of his life and reign.

King Edgar died at Winchester, but he was not buried there with so many of his family, but at the abbey at Glastonbury. The abbot was St Dunstan, who as Archbishop of Canterbury was a major player in the King's reign, and the compiler and celebrant of the 973 coronation. By choosing to be buried at Glastonbury - and it seems right to assume that the King did that - he maintained his identification with the Dunstanian monastic reform and confirmed its alliance with the monarchy.

There appears to have developed something of a cult around King Edgar at Glastonbury, and on the eve of the dissolution of the abbey Under the last two abbots the Edgar Chapel was built on to the east end of the monastic church to contain his remains.

Reconstruction model of Glastonbury Abbey on the eve of the dissolution.

The Edgar Chapel is on the extreme left.

Image:skyscrapernews.com/All rights reserved. Copyright Holder - GNU License

St Mary Magdalene

Today is the feast of St Mary Magdalene.

John Dillon posted these various medieval images of her on the Medieval religion discussion group site. They indicate the wide range of ways in which she has been depicted over the centuries, and the range of media in which she appears, as well as the differing skills and styles of individual artists and craftsmen. Devotion to her appears strong throughout the period, but it appears to have been very strong in the twelfth century, when her shrine at Vézelay was being built and attracting pilgrims; for that seethe online article Vézelay Abbey. By the later middle ages she appears often as a penitent clad in camel hair and with her hair flowing.

I have opened up for this post some of the links, but all are worth looking at - the size of some inhibits opening them all up, and the computer I am using is not very cooperative... :

I have opened up for this post some of the links, but all are worth looking at - the size of some inhibits opening them all up, and the computer I am using is not very cooperative... :

a) as depicted (Noli me tangere; with another Mary) as depicted in a seventh-century icon in St. Catherine's monastery, St. Catherine (South Sinai governorate), Egypt:

b) as depicted (announcing the Resurrection) in a full-page illumination in the earlier twelfth-century St Albans Psalter (betw. 1120 and 1145; Hildesheim, Dombibliothek, MS St. Godehard 1, p. 51):

c) as depicted (addressing the angels before the empty tomb) in the eleventh-century Dionysiou Lectionary (Dionysiou monastery, Mt. Athos, cod. 587, fol. 171v):

d) as depicted in the earlier twelfth-century Melisende Psalter made at the monastery of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem (ca. 1131-1143; London, BL, Egerton MS 1139, fol. 210r):

Detail view:

e) as depicted (announcing the Resurrection) in a panel of the mid-twelfth-century Passion of Christ window (ca. 1145-1155) in the basilique cathédrale Notre-Dame in Chartres:

f) as depicted in the later twelfth-century mosaics (ca. 1182) of the basilica cattedrale di Santa Maria Nuova in Monreale:

g) as depicted in panels of the early thirteenth-century Mary Magdalen window (ca. 1205-1215) in the basilique cathédrale Notre-Dame in Chartres:

1) Washing Jesus' feet:

2) Noli me tangere:

3) The window as a whole:

h) as depicted (upper register; below, Doubting Thomas) in the earlier thirteenth-century so-called Latin Psalter of St. Louis and Blanche of Castile (ca. 1225?; Paris, BnF, ms. Arsenal 1186, fol. 26r):

i) as depicted (at right; at left, St. Sebastian) in a mid-thirteenth-century (ca. 1250-1260) window of the west choir in the Dom St. Peter und St. Paul in Naumburg:

j) as depicted (with eight scenes from her legend) in a late thirteenth-century panel painting (ca. 1280-1285) in the Galleria dell'Accademia in Florence:

k) as depicted (Noli me tangere; image greatly expandable) in a late thirteenth-century copy of French origin of Jacopo da Varazze's _Legenda aurea_ (San Marino [CA], Huntington Library, ms. HM 3027, fol. 78v):

l) as depicted (Noli me tangere) in a fourteenth-century copy of Guiard des Moulins' Bible historiale (Paris, BnF, ms. Français 152, fol. 446r):

m) as depicted by Giotto and assistants in the earlier fourteenth-century Mary Magdalen cycle (betw. 1300 and 1325) in the cappella della Maddalena of the Basilica Inferiore at Assisi (images expandable):

n) as depicted (at left; at right, St. Dorothy) by Ambrogio Lorenzetti on a wing of an earlier fourteenth-century triptych (ca. 1325) in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena:

o) as depicted in the earlier fourteenth-century frescoes (betw. 1326 and 1350) in the church of St. Mary Magdalene in Kanfanar, a locality of Šorići (Istarska županija) in Croatia:

p) as depicted (with another Mary, observing Jesus' burial) in an earlier fourteenth-century fresco (betw. 1335 and 1350) in the sanctuary of the church of the Holy Ascension at the Visoki Dečani monastery near Peć in, depending on one's view of the matter, either the Republic of Kosovo or Serbia's province of Kosovo and Metohija:

q) as depicted (seeing Jesus before the angel-guarded tomb; Noli me tangere) in an earlier fourteenth-century vault fresco (betw. 1335 and 1350) over the altar of the church of the Holy Ascension at the Visoki Dečani monastery near Peć in, depending on one's view of the matter, either the Republic of Kosovo or Serbia's province of Kosovo and Metohija:

Detail views:

r) as depicted (washing Jesus' feet; scenes from her legend) on Lukas Moser's Magdalenenaltar (1432) in the St. Maria Magdalena Kirche at Tiefenbronn (Lkr. Enzkreis) in Baden-Württemberg:

There isa description of the painting at http://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/m/moser/magdalen.html

s) as depicted (scenes from her legend) in the mid-fifteenth-century frescoes of the chapelle Saint-Érige at Auron, Saint-Étienne-de-Tinée (Alpes-Maritimes):

t) as portrayed by Donatello in a mid-fifteenth-century statue (ca. 1457) in the Museo dell'Opera del duomo, Florence:

http://tinyurl.com/pblrfl9

http://tinyurl.com/pblrfl9

Detail view:

For this famous statue, and teh evolution of the image of Mary Magdalen as a penitent see Penitent Magdalene (Donatello)

u) as depicted (at right; at left, St. Godehard) by Giovanni and Luca de Campo in the later fifteenth-century frescoes (1463) of the oratorio di San Bernardo at Briona (NO) in Piedmont:

v) as portrayed (her ascension into Heaven) by Tilman Riemenschneider in a late fifteenth-century sculptural group (ca. 1490-1492) from his dismantled altarpiece for the high altar of the Pfarrkirche St. Maria Magdalena in Münnerstadt (Lkr. Bad Kissingen) in Bayern, now in the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich:

w) A nice, small selection of other late medieval images, in various media, of her ascension (click on the images to enlarge):

x) as depicted (Noli me tangere) by George / Tzortzis the Cretan in the mid-sixteenth-century frescoes (1546/47) in the katholikon of the Dionysiou monastery on Mt. Athos:

Detail view: