Today is the feast of St Brice.

Gordon Plumb posted as follows on the Medieval Religion discussion group about him:

Brice (died 444) was bishop of Tours. He was educated at Martin's monastery at Marmoutiers, though eventually becoming a critic of him. Nevertheless, he succeeded Martin in 397. His long episcopate was marked by ups and downs, with him being accused of adultery on one occasion. Brice went to Rome and was finally vindicated and he returned to Tours after a seven year exile. By 470 his cult was established at Tours, spreading soon to Italy and England. He was almost universally present in English monastic calendars before 1100 and his feast was also in the Sarum calendar.

Wells Cathedral, sII, A2, c.1325:

Wells Cathedral, SIII, 2a-3a, c1340-45:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/22274117@N08/14969512111

John Dillon posted as follows on the same site:

According to Sulpicius Severus (_Dialogi_, 3. 15), Brictius (also Brictio, Briccius, Brixius, etc.; in French and in English usually Brice) was raised by St. Martin of Tours and succeeded him in that see. Attested since the time of bishop St. Perpetuus (d. 491), his cult is closely connected with that of his mentor. St. Gregory of Tours relates a story (Historia Francorum, 2. 1) in which Brictius is said to have maligned Martin both during the latter's lifetime and afterward. As punishment for this, according to Gregory, when Brictius had served as bishop for thirty-three years he was unjustly driven from Tours by its inhabitants who believed, wrongly, that he had impregnated a dedicated virgin who had then carried her child to term. Brictius' accusers were unpersuaded both when he commanded the woman's month-old baby to declare whether he were its father, whereupon the baby said that Brictius was not, and when, to prove his purity, he carried hot coals in his robe to Martin's grave without their causing damage to the garment. His exile lasted for seven years, during which time he betook himself to Rome, confessed to the Pope his sins against Martin's good name, and remained there as a penitent priest. Returning by papal authorization, Brictius entered Tours just after the death of the second of his two successors, resumed his seat, and served happily for another seven years. Thus far Gregory of Tours, whose narrative Jacopo da Varazze follows very closely in his abbreviation in the Legenda aurea (ed. Graesse, cap. 167). Brictius is usually said to have died in about the year 444.

Supplementing Gordon Plumb's post of earlier today, herewith some links to other period-pertinent images of Brictius of Tours (the suffix distinguishes him from his homonyms of Orvieto and Heiligenblut):

a) as depicted (three scenes: accused of fathering the baby; casting hot coals at Martin's grave; commanding the baby to speak) in the late twelfth-century Navarre Picture Bible (1197; Amiens, Bibliothèque Louis Aragon, ms. 108, fols. 243r,244v):

http://www.enluminures.culture.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht3/IRHT_060531-p.jpg

Detail view (accused of fathering the baby):

http://www.enluminures.culture.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht3/IRHT_060529-p.jpg

Detail view (commanding the baby to speak):

http://www.enluminures.culture.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht3/IRHT_060532-p.jpg

b) as depicted (at left; at right, St. Martin of Tours) in an earlier thirteenth-century choir window (w. 217) in the cathédrale Saint-Étienne in Bourges:

c) as depicted (commanding the baby to speak) in an earlier thirteenth-century collection of saint's lives in their French-language translation by Wauchier de Denain (between 1226 and 1250; London, BL, Royal 20 D VI, fol. 127r):

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMIN.ASP?Size=mid&IllID=42726

d) as depicted (commanding the baby to speak) in a late thirteenth-century copy of French origin of the Legenda aurea (San Marino, CA, Huntington Library, ms. HM 3027, fol. 156v):

http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/ds/huntington/images//000919A.jpg

e) as depicted (commanding the baby to speak) in a late thirteenth-century collection of saint's lives in French (1285; Paris, BnF, ms. Français 412, fol. 127r):

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b84259980/f263.item.zoom

f) as depicted (commanding the baby to speak) in a late thirteenth- or early fourteenth-century breviary for the Use of the abbey of Montier-la-Celle (Paris, BnF, Nouvelle acquisition latine 3241, fol. 190v):

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6000034g/f390.item.zoom

g) as depicted (at left; at right, St. Martin of Tours) in an earlier fourteenth-century copy of the Legenda aurea in its French-language version by Jean de Vignay (ca. 1326-1350; Paris, BnF, ms. Français 185, fol. 173r):

http://tinyurl.com/yezr24z

h) as depicted (at right; at left, St. Martin of Tours) in an earlier fourteenth-century copy, from the workshop of Richard and Jeanne de Montbaston, of the Legenda aurea in its French-language version by Jean de Vignay (1348; Paris, BnF, ms. Français 241, fol. 304r):

http://tinyurl.com/yhnr4sg

i) as depicted in a late fourteenth- or early fifteenth-century copy of the Legenda aurea in its French-language version by Jean de Vignay (Rennes, Bibliothèque de Rennes Métropole, ms. 266, fol. 316r):

http://tinyurl.com/p92rwbf

j) as depicted in an early fifteenth-century copy of the Legenda aurea in its French-language version by Jean de Vignay followed by the Festes nouvelles attributed to Jean Golein (c. 1401-1425; Paris, BnF, ms. Français 242, fol. 256r):

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8426005j/f527.item.zoom

k) as depicted (receiving the last rites) in an early fifteenth-century copy of the Elsässische Legenda aurea (1419; Heidelberg, Universitätsbibliothek, Cod. Pal. germ. 144, fol. 194v):

http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/cpg144/0404

l) as depicted (bringing hot coals to Martin's grave) by the court workshop of Frederick III in a mid-fifteenth-century copy of the Legenda aurea (1446-1447; Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, cod. 326, fol. 243r):

http://tarvos.imareal.oeaw.ac.at/server/images/7006892.JPG

m) as depicted (commanding the baby to speak) in a later fifteenth-century copy from Bruges of the Legenda aurea in its French-language version by Jean de Vignay followed by the Festes nouvelles attributed to Jean Golein (ca. 1460-1470; Mâcon, Médiathèque municipale, ms. 3, fol. 44v):

http://www.enluminures.culture.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht6/IRHT_095326-p.jpg

n) as depicted (commanding the baby to speak) in a late fifteenth-century breviary for the Use of Langres (after 1481; Chaumont, Mediathèque de Chaumont, ms. 33, fol. 516v):

http://www.enluminures.culture.fr/Wave/savimage/enlumine/irht6/IRHT_097091-p.jpg

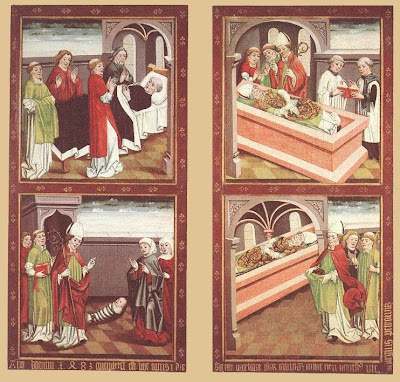

o) as depicted (four scenes) in a late fifteenth-century panel painting (1483) in the Magyar Nemzeti Galéria, Budapest:

Detail view (bringing hot coals to Martin's grave):

p) as portrayed (at right, flanking St. John the Evangelist; at left, St. Martin of Tours) as portrayed in a late fifteenth-century wooden sculpture (1483) from the high altar of the church of St. Martin, Cserény and now in the Magyar Nemzeti Galéria, Budapest:

q) as portrayed in an early sixteenth-century polychromed limewood statue (ca. 1510-1520) in the Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe:

Another list member asked about the the St Brice's Day Massacre during the reign of King Aethelred II (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Brice%27s_Day_massacre): This raises a question: did his cult fall out of favour around 1100, and if so, was it at least in part due to the massacre, or did Saxon saints in general fall out of favour in the wake of the Norman invasion? [The Clever Boy suspects the latter is the answer]

I have posted about the St Brice's Day massacre, and in particular its place in the history of Oxford in

Massacre in Oxford and also tangentially in Decapitating Vikings in Dorset

Finally on the website New Liturgical Movement Gregory DiPippo posted an article about the saint in The Feast of St Brice, St Martin’s Bad Disciple

No comments:

Post a Comment